By LUKE OAKDEN-RAYNER

In the last post I wrote about the recent decision by CMS to reimburse a Viz.AI stroke detection model through Medicare/Medicaid. I briefly explained how this funding model will work, but it is so darn complicated that it deserves a much deeper look.

To get more info, I went to the primary source. Dr Chris Mansi, the co-founder and CEO of Viz.ai, was kind enough to talk to me about the CMS decision. He was also remarkably open and transparent about the process and the implications as they see them, which has helped me clear up a whole bunch of stuff in my mind. High fives all around!

So let’s dig in. This decision might form the basis of AI reimbursement in the future. It is a huge deal, and there are implications.

Uncharted territory

The first thing to understand is that Viz.ai charges a subscription to use their model. The cost is not what was included as “an example” in the CMS documents (25k/yr per hospital), and I have seen some discussion on Twitter that it is more than this per annum, but the actual cost is pretty irrelevant to this discussion.

For the purpose of this piece, I’ll pretend that the cost is the 25k/yr in the CMS document, just for simplicity. It is order-of-magnitude right, and that is what matters.

A subscription is not the only way that AI can be sold (I have seen other companies who charge per use as well) but it is a fairly common approach. Importantly though, it is unusual for a medical technology. Here is what CMS had to say:

As CMS notes here, they don’t have much experience with technology-by-subscription reimbursement. I don’t know for sure if this is the first time they have had to consider this issue, but it might be. Certainly the CMS/Medicare model is to reimburse per service provided, so dealing with subscriptions is outside of their wheelhouse.

It is worth noting that other models are under review. For example, frequent flyer in medical AI news IDx (recipients of the first “autonomous AI” FDA approval) have applied for a fee-for-service payment model under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS – pdf link explaining this payment system). This appears to be more like the “pay per procedure” funding model we are used to with mammography CAD (in this case, the proposed rule is for the provider to receive a reimbursement of $11-$34^ for each use of the IDx algorithm).

But regardless, CMS is blazing a new trail with Viz.

Let’s revise what they plan to do:

- Each year, they will determine the average number of patients who are given an AI-assisted scan per subscription (Viz is selling subscriptions by site, meaning each hospital needs a subscription)

- They will divide the subscription cost by the number of patients to get the per patient cost

- They will reimburse at this per patient cost for the next year

As far as mechanisms to deal with a yearly subscription cost on a per patient basis, it sounds fine, at least at first glance.

It’s complicated

As anyone who deals with healthcare as a system would appreciate, it is always much more complicated than it sounds.

An uncomplicated read of the rules might suggest that big hospitals are going to make out like bandits here. $1000 is less than nothing to a hospital, but the scan volumes estimated in the CMS documents are low. CMS estimates that hospitals would use this technology on less than 100 patients per year. Here is the indication for use from the FDA:

“ContaCT is indicated for patients older than 22 years of age. Additionally, the patient should have undergone a stroke protocol assessment after presenting to the Healthcare Facility and receive a head and neck CT angiogram (CTA) during their stroke protocol assessment.”

Indicated patient population, FDA

I asked around, and even mid-sized hospitals are scanning 1500-2000 code-strokes^^ per year. Large stroke centres are doing more than 5000.

Which would, I naively assumed, mean that for an outlay of 25k the hospital will bring home a fresh 5 mil. Tasty.

But… it’s complicated.

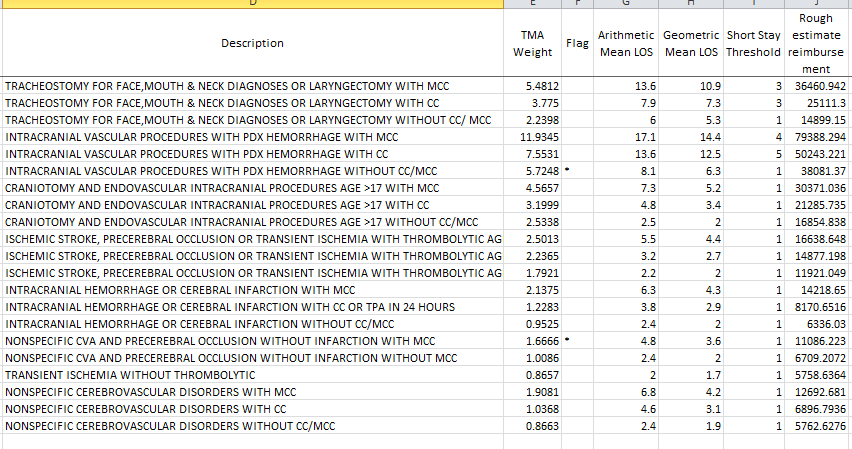

It turns out that far fewer patients than this are actually eligible for the reimbursement. Here is some Medicare data supplied by Chris:

There are multiple exclusion factors, so in this case a large stroke centre might do 6,300 code stroke studies, but only around 4,000 get the scan that ContaCT uses to detect blockages. About half of these patients are covered by Medicare, and only half again go on to inpatient admissions. Then there is the final eligibility step, which drops the number of reimbursable patients from 1,000 to only 142.

CMS rules state that they will only pay a New Technology Add-on Payment (NTAP) if the patient was a loss-maker for the hospital – that is, they cost more to treat than the hospital receives in payments already. Patient payments from Medicare are received as set-value bundles for specific encounter types, called DRGs (diagnosis related groups). You can see the DRG list here (pdf link), an explanation of all things DRG here (pdf as well), and a good summary of the NTAP system here.

In general, surgical reimbursements in the US are higher than medical reimbursements, which is important because a thrombectomy is considered surgical rather than medical. A thrombectomy (also called clot retrieval) is when an interventional neuroradiologist (INR) physically removes the clot from the brain, restoring blood flow.

So if everything goes well and ContaCT gets a patient to the INR in time for a thrombectomy, the hospital gets a higher reimbursement, but is less likely to receive the ContaCT NTAP.

This makes the NTAP reimbursement something of a consolation prize. The hospital will get the extra $1000, but because of longer hospitalisations and worse outcomes without thrombectomy, the shortfall is often more than the NTAP will cover*. As a general rule, this will be more important at spoke hospitals (small referrer centres) who will have a higher proportion of loss-making patients, whereas at large stroke centres they will typically get higher reimbursements as the referred patients undergo more thrombectomies, but will receive fewer NTAPs. In Chris’ figures above, the spoke hospital could receive around half as much NTAP reimbursement as the hub, despite scanning 6 times fewer patients.

So, the amount of reimbursement is likely much lower than the naive read suggested, but this doesn’t make the NTAP a bad thing. No hospital admin will turn down extra cash.

But it does mean that the main selling point isn’t the reimbursement, particularly at the hub hospitals. It is the chance to get more patients to thrombectomy that is the real value-maker.

Generating value

All of this is from Chris (the Viz CEO), so take with as big a grain of salt as you would like, but one number really jumped out at me during our talk: at large stroke hubs with ContaCT in use, thrombectomy rates have increased by 50-60%**.

This means that patients are truly being retrieved quicker, receiving better treatment, and in turn hospitals are getting larger reimbursements for their care. They are thus more likely to cover costs or even make a profit on these patients, unrelated to the NTAP. I only have a rough sense of how this might play out, but the difference to the hospital bottom-line could be much larger than the estimated $150,000 in NTAP payments.

I’ve written many times about the struggle to generate value for AI vendors, but it seems like Viz isn’t facing this problem at all, which is shown in the other number that Chris told me: ContaCT, without the NTAP, is already deployed in 500 hospitals across the US!

What could go wrong?

So Viz will do ok out of this, but ContaCT has some pretty unique attributes. What about the funding model broadly? Does it make sense to use NTAP reimbursement to pay for subscription services? Will it incentivise both the use of good technology, and the development of useful AI models?

The US payment system is so complicated that there can be no universal interpretation or guidance, since the NTAP system relies on DRGs, loss-making, and yearly estimations of unit costs to determine reimbursement value. But as a broad simplification, we can see a few things:

- This is a funding model that rewards volume of use, rather than value to patient. I’m not a health economist, but this issue has been hotly debated for many years. In this case, there is pretty good evidence that saving time saves money (estimated at $1059 per minute of delay to thrombectomy), but the broader point remains.

There is another possible problem though.

- Reimbursements are determined by estimates of volume per subscription. Thus, reimbursements will be higher at hubs than spokes, despite the same subscription cost. Furthermore reimbursements may come down as volumes increase (as more large providers deploy the system).

- If reimbursements fall, smaller providers with low volumes may be unable to recoup costs.

- Developers will have the choice to

- maintain subscription costs, resulting in falling reimbursement to cost ratios for healthcare providers. This is likely to result in fewer subscriptions.

- reduce subscription costs to incentivise use by smaller providers.

- do the usual subscription service tomfoolery like having “premium” and “basic” subscription tiers which allow for smaller providers to get cheaper access, but are essentially just “pay-per-use” contracts by stealth.

The combination of the first two points is not particularly promising for the funding model as each leads to falling revenue for the developers. As Elliot says above, this could be the start of a race to the bottom***.

On the flip side, it is a clear mechanism to generate revenue for AI startups, which has been a serious challenge for most.

But it may also be, as appears to be the case with Viz, that CMS NTAP approval is less a mechanism by which startups achieve viability and more an endorsement of AI startups that were already viable in the first place. Time will tell.

^ Part of what makes the Viz finding model hard to wrap your head around is the difference in reimbursements. IDx gets up to 30 bucks, Viz gets 1000! It isn’t as weird as it sounds though.

^^ A “code stroke” is a rapid response protocol for suspected stroke, and usually includes an unenhanced CT brain, a carotid/COW CT angiogram, and a CT perfusion study where this is available. This sort of study is what ContaCT is approved for by the FDA.

* Worth noting here that the loss is unrelated to ContaCT, and was going to happen anyway. The $1000 is extra money the hospital wouldn’t have, which offsets the loss at least a little. Also worth noting that as the figures from Chris showed, the reimbursement of patients is often below $1000, as it covers up to 65% of the loss the hospital makes on the patient, to a maximum of $1000.

** This is a really interesting element of the story. Do we need to train 50% more interventional neuroradiologists? AI creates jobs!

*** This is unlikely to be a problem with Viz, where the particular interplay of DRGs and reimbursements provides payments to spoke centres at a relatively higher rate, supporting the small providers to continue their subscriptions. It could be a serious issue for other AI vendors if the funding model is used more widely.

Luke Oakden-Rayner is a radiologist in South Australia, undertaking a Ph.D in Medicine with the School of Public Health at the University of Adelaide. This post originally appeared on his blog here.

Categories: Uncategorized

This is a great take on a very complicated matter of reimbursement. It really helps put into perspective what the true dollar amount of the CMS NTAP means for a company like Viz.ai

Seems like the true value generation after all is that more patients are going to the interventional suite for mechanical thrombectomy. Wondering how many other procedures have the potential to treat other disease states that are currently not being used to their maximum potential–Will Viz.ai capitalize on these other areas?

Quite fascinating to see the dynamics of cash and how it can mean so many different things for different hospitals. One aspect that I also envision will play a role in the future will be that companies like Viz gain access to amounts of data previously unheard of that can create sample sizes from such varied geographies. What are the ethical implications of using these data to potentially produce algorithms that put them astronomically ahead of any other competitor? And how will the data generators (individual hospitals, but even more patients and their families) be compensated for this competitive advantage?