By MATTHEW HOLT

I am dipping into two rumbling controversies that probably only data nerds and chronic care management nerds care about, but as ever they reveal quite a bit about who has power and how the truth can get obfuscated in American health care.

This piece is about the data nerds but hopefully will help non-nerds understand why this matters. (You’ll have to wait for the one about diabetes & chronic care).

Think about data as a precious resource that drives economies, and then you’ll understand why there’s conflict.

A little history. Back in 1996 a law was passed that was supposed to make it easy to move your health insurance from employer to employer. It was called HIPAA (the first 3 letters stand for Health Insurance Portability–you didn’t know that, did you!). And no it didn’t help make insurance portable.

The “Accountability” (the 1st A, the second one stands for “Act”) part was basically a bunch of admin simplification standards for electronic forms insurers had been asking for. A bunch of privacy legislation got jammed in there too. One part of the “privacy” idea was that you, the patient, were supposed to be able to get a copy of your health data when you asked. As Regina Holliday pointed out in her art and story (73 cents), decades later you couldn’t.

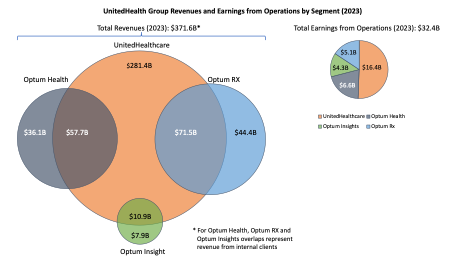

Meanwhile, over the last 30 years America’s venerable community and parochial hospitals merged into large health systems, mostly to be able to stick it to insurers and employers on price. Blake Madden put out a chart of 91 health systems with more than $1bn in revenue this week and there are about 22 with over $10bn in revenue and a bunch more above $5bn. You don’t need me to remind you that many of those systems are guilty with extreme prejudice of monopolistic price gouging, screwing over their clinicians, suing poor people, managing huge hedge funds, and paying dozens of executives like they’re playing for the soon to be ex-Oakland A’s. A few got LA Dodgers’ style money. More than 15 years since Regina picked up her paintbrush to complain about her husband Fred’s treatment and the lack of access to his records, suffice it to say that many big health systems don’t engender much in the way of trust.

Meanwhile almost all of those systems, which already get 55-65% of their revenue from the taxpayer, received additional huge public subsidies to install electronic medical records which both pissed off their physicians and made several EMR vendors rich. One vendor, Epic Systems, became so wealthy that it has an office complex modeled after a theme park, including an 11,000 seat underground theater that looks like something from a 70’s sci-fi movie. Epic has also been criticized for monopolistic practices and related behavior, in particular limiting what its ex-employees could do and what its users could publicly complain about. Fortune’s Seth Joseph has been hammering away at them, to little avail as its software now manages 45%+ of all encounters with that number still increasing. (Northwell, Intermountain & UPMC are three huge health systems that recently tossed previous vendors to get on Epic).

Meanwhile some regulations did get passed about what was required from those who got those huge public subsidies and they have actually had some effect. The money from the 2009 HITECH act was spent mostly in the 2011-14 period and by the mid teens most hospitals and doctors had EMRs. There was a lot of talk about data exchange between providers but not much action. However, there were three major national networks set up, one mostly working with Epic and its clients called Carequality. Epic meanwhile had pretty successfully set up a client to client exchange called Care Everywhere (remember that).

Then, mostly driven by Joe Biden when he was VP, in 2016 Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act which among many other things basically said that providers had to make data available in a modern format (i.e. via API). ONC, the bit of HHS that manages this stuff, eventually came up with some regulations and by the early 2020’s data access became real across a series of national networks. However, the access was restricted to data needed for “treatment” even though the law promised several other reasons to get health data.

As you might guess, a bunch of things then happened. First a series of VC-backed tech companies got created that basically extract data from hospital APIs in part via those national networks. These are commonly called “on-ramp” companies. Second, a bunch of companies started trying to use that data for a number of purposes, most ostensibly to deliver services to patients and play with their data outside those 91 big hospital systems.

Which brings us to the last couple of weeks. It became publicly known among the health data nerd crowd that one of the onramp companies, Particle Health, had been cut off from the Carequality Network and thus couldn’t provide its clients with data.

Continue reading…