By VINCE KURAITIS and DEVEN McGRAW

Two years ago we wouldn’t have believed it — the U.S. Congress is considering broad privacy and data protection legislation in 2019. There is some bipartisan support and a strong possibility that legislation will be passed. Two recent articles in The Washington Post and AP News will help you get up to speed.

Federal privacy legislation would have a huge impact on all healthcare stakeholders, including patients. Here’s an overview of the ground we’ll cover in this post:

- Why Now?

- Six Key Issues for Healthcare

- What’s Next?

We are aware of at least 5 proposed Congressional bills and 16 Privacy Frameworks/Principles. These are listed in the Appendix below; please feel free to update these lists in your comments. In this post we’ll focus on providing background and describing issues. In a future post we will compare and contrast specific legislative proposals.

Why Now?

A number of factors have contributed to bringing the privacy issue to the near boiling point:

Techlash and Surveillance Capitalism. Facebook scandals, Cambridge Analytica, Russian election interference, tech addiction, data breaches — all have contributed to the techlash against Silicon Valley giants and have raised growing calls for regulation.

A central theme is the growing public understanding of how personal data has been harvested. In a recent Blis survey, 63% of consumers responded that they were “more aware” of how personal data is used by companies versus a year ago.

The crescendo of criticisms is only getting louder. Harvard Law professor Shoshana Zuboff’s recently published book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism takes techlash to new levels. She writes: “Surveillance capitalists soon discovered that they could use these data not only to know our behavior but also to shape it.”

European Regulations. Europe now has the world’s strongest privacy and data protection regulation. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in May 2018.

State Regulation. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which goes into effect in January 2020 and is modeled after GDPR, has broad reach and has large companies that collect health (or health-related) information scrambling for federal relief. The State of Washington and others appear to be following suit.

Tech companies are realizing that the status quo is not an option. The United States does not have a comprehensive federal data protection law. Instead, the U.S. legislative framework for privacy and information security consists of multiple laws that regulate the private sector primarily on a sector-by-sector basis, with multiple regulatory authorities dedicated to oversight.

Six Key Issues for Healthcare

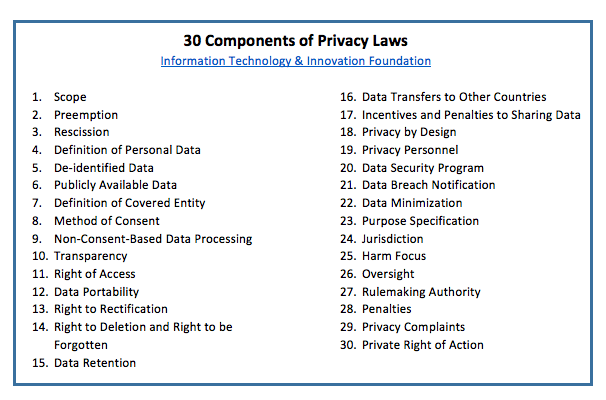

What provisions are likely to be included in a new federal privacy law? The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) recently released a report that lists 30 possible components of privacy laws (see the callout box).

Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, https://itif.org/publications/2019/01/14/grand-bargain-data-privacy-legislation-america

The ITIF report provides explanations of each of these components. We’ll reference many of them in our list of six issues that we think will be particularly important for patients and other healthcare stakeholders:

- Is There Federal Preemption of State Legislation?

- Is All or Part of HIPAA Rescinded?

- How Are Interests ACROSS Stakeholder Groups Addressed?

- How Are Interests WITHIN Stakeholders Groups Addressed?

- How are Next Generation Technologies Addressed?

- How Will New Privacy Legislation be Enforced?

Let’s look at these individually.

1) Is There Federal Preemption of State Legislation?

This promises to be a contentious issue. A simple way to look at this — is federal law a floor or a ceiling for consumer rights?

Tech companies are fearful of unharmonized legislation passed in U.S. states and countries across the world. They would prefer to see one federal law that prohibits states from passing their own laws. Global companies would prefer to see one federal law that is in harmony with GDPR.

Fearful of weak federal legislation, consumer advocates at least initially will prefer to see federal legislation that continues to allow states to pass stronger laws. 16 privacy groups submitted a letter to Congress supporting strong state privacy laws and opposing federal preemption.

This opposition to federal preemption could soften when considering federal legislation that would provide strong consumer protections.

2) Is All or Part of HIPAA Rescinded?

HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy, security and breach notification regulations) does not protect all health related data — it only covers health information in the hands of HIPAA-covered entities (primarily care providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses) and their business associates (contractors who collect health information to perform services on a covered entity’s behalf). It does NOT protect health information in the hands of entities not specifically covered by HIPAA. For example, HIPAA does not cover health information in consumer-facing apps. HIPAA also does not apply to data that has been de-identified (rendered very low risk of re-identification).

How might federal privacy legislation affect HIPAA? That’s something of a wildcard for now. It’s possible that privacy legislation could expand HIPAA-like protections to non-HIPAA data, or it’s possible that federal legislation could perpetuate loopholes in not providing specific protections for health-related data.

Some are calling for a GDPR-like law that covers all personal data and eliminating all sector specific privacy laws. In the interests of achieving a uniform, national privacy scheme, the ITIF Report specifically recommends rescinding HIPAA:

…federal privacy legislation should create a common set of federal protections for all types of data. This will mean removing duplicative or conflicting rules. To accomplish this, federal privacy legislation should sunset other sector-specific privacy laws, such as GLBA, HIPAA, and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), and bring the industries covered by those rules under a single federal data privacy law.

3) How Are Interests ACROSS Stakeholder Groups Addressed?

In the broadest sense, privacy legislation will be about meeting interests of consumers/patients vs. those of technology companies. Many tech companies increasingly are recognizing the need to reestablish and maintain consumer trust — and that this requires clearly delineated, transparent, and auditable practices. But companies and consumers/patients are likely to disagree on exactly how to build and maintain that trust.

Components of privacy legislation that will be of most interest to consumers/patients relate to personal control over data:

- Data portability

- Rights to correct/rectify errors

- Rights to delete certain types of data

- Consents to data sharing and use

- Requirements that data is used only for specified purposes

- Limitations on secondary uses of data

- Time limits to data retention

- Requirements to gather/use/share as little data as possible

- Data security

- De-identification of data

- A private right of action for violations

Components of privacy legislation that will be of most interest to tech companies and many healthcare incumbents include:

- Harmonization of requirements across states and across countries (see the discussion on preemption above)

- Minimizing compliance costs

- Freedom to innovate

- Few limitations on data gathering/use/sharing

- Limiting penalties and private rights of action

4) How Are Interests WITHIN Stakeholders Groups Addressed?

Within major stakeholders in the HIPAA ecosystem there are dividing points of view. We’ll share a few examples.

Even those who advocate for a stronger federal law differ in their preferences:

Privacy maximalists will prefer the most stringent protection of consumer data. They will prefer to give individual patients as much control as possible in how their data is shared and used. “We’d like to see laws that require data to be gathered only for specific purposes, that these specific purposes be spelled out to patients, that patients must specifically consent to gathering and sharing of data, that data not be used beyond purposes specified, and that certain types of data be deleted after a specified time period.”

Privacy balancers will point out tradeoffs among components of privacy and will weigh costs and benefits. “We recognize that health data has significant potential to advance medicine and science; thus researchers and conductors of clinical trials need reasonable access to large sets of patient data.” (See the discussion in the next section)

Healthcare providers also are unlikely to have uniform views of privacy legislation. Some likely will welcome strengthened privacy protections. “We’re truly working to make our health system more ‘patient centric’. Specifying patient rights to data will help us to protect our patients and to carry out their wishes about how their data is shared and used.”

Other providers who might view data in medical records as “theirs” might prefer the status quo. “The ambiguities about ownership of medical information work to our advantage. We treat medical data as if it’s ‘ours’ and we see that it’s to our competitive advantage to do so.”

Health plans may be more likely to have consistent positions, supporting provisions that impose privacy rules on entities currently outside the HIPAA coverage bubble but preferring to continue to be governed by HIPAA versus being covered by new, less familiar rules. “HIPAA works just fine to protect information collected by health plans, but there should be a level playing field for all companies collecting health information.”

In the tech world, some companies have embraced surprisingly strong views favoring consumer protections:

Apple CEO Tim Cook: “We all deserve control over our digital lives. That’s why we must rein in the data brokers….Consumers shouldn’t have to tolerate another year of companies irresponsibly amassing huge user profiles, data breaches that seem out of control and the vanishing ability to control our own digital lives.”

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella: I am hopeful that in the United States we will have something that’s along the same lines [as European GDPR regulations]. In fact, I hope that the world over we all converge on a common standard.”

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff:

Benioff at #WEF19 ‘Facebook and Twitter need to change their CEO’s and their boards. Why dont they get on a stage and say: Im sorry, we are now going to put trust first?’ pic.twitter.com/cGBJQNN6A5

— Marietje Schaake (@MarietjeSchaake) January 24, 2019

These are just a few examples. However, it is unclear whether these strong commitments translate into support for a strong federal privacy law.

5) How are Next Generation Technologies Addressed?

Next generation technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and analytics offer alluring promises of advancements in medicine and healthcare. Law professors Price and Cohen describe some of the potential:

Big data enables more powerful evaluations of health care quality and efficiency, which then can be used to promote care improvement. Currently, much care remains relatively untracked and underanalyzed; amid persistent evidence of ineffective treatment, substantial waste, and medical error, understanding what works and what doesn’t is crucial to systemic improvement.

Regulations often lag the capabilities of new technologies. As we mentioned in the introductory section, there are also significant concerns relating to techlash and surveillance capitalism. But these next generation technologies raise issues of discrimination and fairness which are related to but go beyond privacy concerns – for example, use of big data to make health care resource allocation decisions that exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities in care.

Some of the issues we see relating to potential privacy legislation include:

- Will data that are de-identified or anonymized (and how those terms are defined) remain more widely available for big data uses?

- Will the legislation address discrimination, or will we be left with merely the protections of GINA, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the Affordable Care Act, all of which have loopholes?

- Does the legislation deal with the potential for bias in next generation technologies, such as by requiring fairness and/or transparency in the algorithms used to make decisions about individuals and/or populations?

6) How Will New Privacy Legislation be Enforced?

Here are some key questions to consider:

What agency or agencies will have authority to enforce health related aspects of new privacy legislation? Likely candidates include the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) within Health and Human Services (HHS), or perhaps a newly created agency.

What amount and types of resources will be available to enforce new legislation?

Will the enforcing agency have ongoing rulemaking authority to address gaps in legislation and/or new technologies or industry practices?

Will patients be given a private right of action, i.e., the right to take companies to court?

Will state attorneys general and agencies be permitted to investigate and enforce violations of federal rules?

What’s Next?

Privacy legislation debates likely will become highly visible in 2019. A recent Harris/Finn poll found that “privacy of data” was the #1 issue that American companies should address, with 65% of respondents indicating it was “very important”.

The list of 30 components of privacy legislation speaks to the complexity of issued involved, and it also highlights many opportunities for compromise.

The ITIF Report described Congress’ key task as being “to balance competing goals such as consumer privacy, free speech, productivity, U.S. economic competitiveness, and innovation.”

This won’t be an easy task and we expect that it will take a while to play out. It might take longer than one year to develop Federal privacy legislation. It’s also possible that privacy legislation could become an important issue in the 2020 election.

We encourage you to pay attention, and to keep this important issue on your radar!

APPENDICES

Proposed and Pending Bills

Frameworks/Principles

Center for Democracy & Technology

Computer & Communications Industry Association

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Electronic Privacy Information Center

Information Accountability Foundation

Information Technology Industry Council

Vince Kuraitis, JD/MBA (@VinceKuraitis) is an independent healthcare strategy consultant with over 30 years’ experience across 150+ healthcare organizations. He blogs at e-CareManagement.com.

Deven McGraw , JD, MPH, LLM (@healthprivacy) is the General Counsel and Chief Regulatory Officer at Ciitizen (and former official at OCR and ONC). She blogs at ciitizen.com.

Categories: Uncategorized

This is very valuable, thank you Deven and Vince. Another item: Should a patient have the right to say who they are? Create my identity to be shared so that I can log on to all of my portals and API the same way?

The draft NPRM is a breakthrough toward interoperability because it enables the Federal Health Architecture to implement patient-directed health information exchange as a condition of participation unilaterally – avoiding a second decade of foot-dragging by special interests. Cerner at the VA would just have to go along.

CMS actuaries predict a $6 Trillion / 19.4% of GDP healthcare sector by 2027. I have yet to find a single person who thinks that is sustainable for the US economy and political system. A revolution will come. It could be ultra-left or ultra-right in how it introduces price cuts, but it will happen long before anyone figures out how to “bend the cost curve” by fiddling with regulatory capture.

The current administration has only a few months to steer the revolution in a market-driven direction that actually enables price and quality competition. Patient-directed interoperability and data use transparency could be in place by 2021 without any obvious need for congressional action beyond existing 21C Cures.

The roadmap is described in my recent post https://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2019/02/22/oncs-proposed-rule-is-a-breakthrough-in-patient-empowerment/ I’m an optimist and betting HHS will do it. Join me.

David, Thanks for your comment. Agree — legislation in 2019 is not a done deal. Keeping my fingers crossed. We’ll continue to write about this.

Excellent overview of key issues and potential solutions. I am (as always) skeptical that we will achieve meaningful change anytime soon (esp. in the swamp-by-the-Potomac). The lag in serious implementation by many companies after the GDPR effective date is indicative of the long road ahead, even if we get the perfect new law enacted. I fear that we will collectively not be able to get out of our own way and achieve consensus on a meaningful federal privacy law that preempts state law. But I’d love to be surprised on this one.

Good Question !

Youll Definitely get an answer on my Blog too in some days !

https://momsbosom.com/

So does this mean I should just give up on the fantasy of some day being able to see the cath results from the hospital across town before I have to take the urgent exploratory lap to the OR?

Steve

Dave, Thanks for commenting. I’m also reading Surveillance Capitalism. The book explicitly is a very thorough expose of the problems and is intended to educate, but doesn’t offer a lot of deep answers.

Federal legislation for data/privacy protection would be a good start…but it’s not the final answer.

And yes, Zuckerberg has lost all credibility and trust. As a start, FB needs an “under new management” sign.

Lygeia, thanks for your positive words!

Lymepolicywonk, agree that de-identification comes with risks of harm….and re-identification is especially doable with health data given the specificity and uniqueness of data.

I’m impressed with the registry you’ve established. More generally, I think that you illustrate the need for independent 3rd parties to oversee health research projects.

William, you raise good points. Part of the complexity of potential legislation is that there are so many diverse interests and not easily foreseeable circumstances.

And, while other types of data about us have been gathered for decades, health care data harvesting is still a relatively new field — most health record data hasn’t been digitized until recently and much of it still isn’t…and we’ve got a long way toward getting past silos of non-interoperable data. As you note security is critical. Risks and opportunities.

Deven and Vince, thank you so much. These are huge implications and the time is ripe.

Additions:

1. Patients need to have enough equity ownership in their medical records such that they can get together as a class and, perhaps with their attorneys, investigate the data, write papers, present facts to Congress or state legislatures and, in fact, ultimately change behavior of their health plans or insurers or hospitals. They, therefore, need to be able to study the data and do things with it. Symmetry. Now we have huge firms and agencies using and profiting from the data. The patients need to be able to do the same thing.

An example: Say there is a health plan Thrive. Thrive owns some nursing homes and some outpatient laboratories and image centers. There are similar outside competing facilities in the same service area. Patients get wind that referrals from Thrive are always to its own facilities where prices are notoriously high. A study is needed.

Or say the community finds thru anecdotal reports in the newspapers that the ER of its dominant hospital is not following EMTALA principles and is demanding payment guarantees prior to service. A study is needed.

2. The definition of data should extend to financial data associated with the patient’s clinical data. This is what is demanded of the patients and should be what the patients are demanding from the insurer or provider. Again, symmetry. And again, the notion of ownership of the data needs to be studied.

3. We need to have accountability processes so that if failure of data security occurs, some consequencies happen.

4. We need to be able to test security by using contracting hacking services.

This is a terrific overview of the issues. Thank you. I would add that just because data is de-identified does not mean it can not do harm. It has less of a chance of creating personal harm through discrimination but it still has the potential to do harm to a community–especially a stigmatized community. For example, our patient registry has enrolled over 12,000 patients in a trust based data sharing model that specifies that their data will only be used for the benefit of the patient community as determined by patients. This means that researchers and research projects are vetted to prevent researcher bias that might serve to further marginalize the community or diminish, dismiss or trivialize patient concerns. This is a bit like community participatory research. This applies to our community, which is highly stigmatized, but also to other stigmatized or targeted communities such a native Americans, African Americans, mental health communities, LGBTQ communities, addicts etc. So there is individual autonomy and also community stewardship to protect communities at risk for data misuse that harms their community by biased or insensitive researcher who fail to understand or hold the community interests at the center.

Also nice to reconnect with Deven who taught me so much when I chaired the patient privacy panel at PCORI.

Thanks, Deven and Vince. This is a valuable overview of the status quo!

Thank you both, very much, for this schooling!

I’ve started reading Surveillance Capitalism and stopped to read Zucked, which is infinitely more informative about the specifics of Facebook – especially useful because it’s written not by someone who’s reflexively hostile to the topic but by Silicon Valley guru Roger McNamee, who’s a fan of what FB has done in the past, coached Zuck in FB’s early years, and brought Sheryl Sandberg in. When HE says they’ve gone too far – way too far – it has additional oomph.

Plus, having worked myself in Google AdWords (successfully, with Appy Award), I get the whole idea.

I’ll repeat here what I just said about this on Twitter:

@MightyCasey just flagged me on this 2014 WaPo article on Zuck’s view of privacy, claiming what we need (and have!) is “control,” not privacy. It’s totally panned out consistently in the next 5 years.

My view: if there were a shred of truth to the “control” claim, they’d SHOW us what they’re sharing, and give us the ability to say no (aka to control it!) BEFORE they share it.

Note too that last week the British government busted them for “willfully and knowingly” ignoring users’ privacy settings. So much for “control,” eh?