By PHUOC LE, MD and BROOKE WARREN

In the 2020 Summer Olympics, we will undoubtedly see large, red circles down the arms and backs of many Olympians. These spots are a side-effect of cupping, a treatment originating from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to reduce pain. TCM is a globally used Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM), but it still battles its critics who think it is only a belief system, rather than a legitimate medical practice. Even so, the usage of TCM continues to grow. This led the National Institute of Health (NIH) to sponsor a meeting in 1997 to determine the efficacy of acupuncture, paving the way in CAM research. Today, there are now over 50 schools dedicated to teaching Chinese acupuncture in the US under the Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture & Oriental Medicine.

While TCM has seen immense growth and integration around the globe throughout the last twenty years, other forms of CAM continue to struggle for acceptance in the U.S. In this article we will focus on Native American/Indigenous traditional medical practices. Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients should not have to choose between traditional and allopathic medicine, but rather have them working harmoniously from prevention to diagnosis to treatment plan.

It was not until August of 1978 that federally recognized tribal members were officially able to openly practice their Indigenous traditional medicine (the knowledge and practices of Indigenous people that prevent or eliminate physical, mental and social diseases) when the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) was passed. Prior to 1978, the federal government’s Department of Interior could convict a medicine man to a minimum of 10 days in prison if he encouraged others to follow traditional practices.

It is difficult to comprehend that tribes throughout the U.S. were only given the ability to openly exercise their medicinal practices 41 years ago when the “healing traditions of indigenous Native Americans have been practiced on this continent for 12,000 years ago and possibly for more than 40,000 years.”[1]

Since the passage of AIRFA, many tribally run clinics and hospitals are finding ways to incorporate Indigenous traditional healing into their treatment plans, when requested by patients.

Examples include the Puyallup Tribe of Indians’ Salish Cancer Center in Washington and the Southcentral Foundation, a nonprofit Native-owned healthcare organization in Alaska. At the Salish Cancer Center, Native healers are brought in from various tribes around the US twice a month, allowing patients to adhere to their own tribal protocol and healers to have direct communication with oncologists at the center.

While we may be wondering how effective bringing Native healers is for patient outcomes, these data are seldom shared. Traditional healing is a very sacred practice, and for both the patient and healer, many tribal members choose not to share information publicly.

So rather than attempt to figure out the efficacy of integrating Indigenous traditional healing and allopathic medicine, we share a story about when they worked together synergistically:

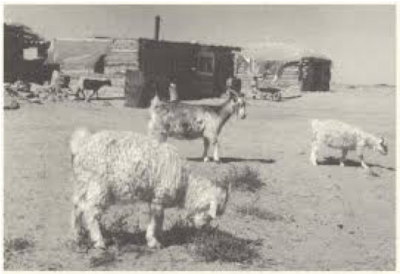

On the Navajo Reservation in 1952, there was a tuberculosis (TB) epidemic. The TB rate for the Navajo population was ten times the rate of occurrences in the Caucasian population in the same geographic region. 302/100,000 Navajos had TB compared to 30/100,000 Caucasians. Dr. Walsh McDermott, from Cornell Medical College, heard about this emergency of untreated TB and organized to bring a group comprised of doctors and researchers to the reservation from Cornell Medical College. This came to be known as the Many Farms Demonstration Project.

Unlike the federal government, Dr. McDermott welcomed traditional healers and community leaders into his work and acquainted them with the procedures being used.

This relationship proved beneficial to ending the epidemic because the traditional healer was able to solve a problem that the Western-trained doctors could not. When lightning struck near the hospital, Dr. McDermott’s patients began to flee because of their traditional belief that lightening brings misfortune. A Navajo medicine man was brought in to bless both the hospital and patients, and to appease the spirits. The patients, trusting their medicine man’s healing of the land and space, subsequently came back in because they were confident that there was no more danger. This made it so their TB treatment could begin again.

From a Western science perspective, there may not be many randomized controlled trials to prove the efficacy of Indigenous traditional medicine. The example above, though, clearly shows that the use of Western science in isolation would not have produced the cures it had sought. For allopathic medicine to have its intended effects in improving health outcomes of populations who use CAM, it must work harmoniously with CAM and respect it. As the Indian Health Service lays out in its policy, the “respect and acceptance [of] an individual’s private traditional beliefs become a part of the healing and harmonizing force within his/her life.”

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913884/

Internist, Pediatrician, and Associate Professor at UCSF, Dr. Le is also the co-founder of two health equity organizations, the HEAL Initiative and Arc Health.

Brooke Warren is a Native American Studies major and recent graduate of UC Davis. She is currently an intern at Arc Health.

This post originally appeared on Arc Health here.

Categories: Medical Practice

Apologies for my late response! But yes, I too believe that studying all types of medicine is necessary (as long as it is done with the approval of the community the healthcare methods are coming from).

Thanks for your reply, Brooke. We are really all chemistry, don’t you think? Even placebos are doing chemistry of some sort in the neurons or synapses.? or they may be re-configuring neural pathways to hit the amygdala or something. I just don’t want to veer too much from genes and proteomes and metabolomes. I’m sure some of this traditional health care works well and is fundamentally science-based, but we have to study and dissect it to the chemical level too, just as we are doing with allopathic care. No discipline should escape having its chemistry examined and explained. Even thoughts and beliefs in God and spirits, if they work, are going to ultimately have a chemical root….because that is what we are. We can believe in the soul—I do—but if it is affecting illness and disease then it has to be working through chemistry.

Hi Dr. Palmer– thank you for your comment on our blog post!

In response to some of your questions, I personally do not consider traditional medicine as a synonym to ancient medicine or as being quaint.

Many traditional medicines have been utilized by their communities for thousands of years longer than allopathic or other western-based medicines. In many communities, it takes years to practice their medicine— years of learning and training, making it more than something run out of Disneyland. And, what they are doing is not a ‘myth’ or ‘fairytale’. Many use their own version of the scientific method that we call upon today and use their own methods of deduction and testing in order to understand the world around them.

Also, I think it is a misconception to believe that traditional medicine has not progressed throughout time and adapted to modernity and daily life today. There have been thousands of Indigenous scholars who have extensively researched and found ways to see how their knowledge systems, which have been passed down for generations, can help people today and in the future.

Therefore, I think western-based medicine must be open to the possibility that it combined with a patient’s traditional medicine could be more beneficial that one standing alone. No practice of medicine is perfect. I hope that we can find the strengths among them and address the health outcomes of communities here in the US and around the globe!

I enjoyed this post but we have to extrapolate a little: Do you believe that any ancient and revered medical practice or custom should be OK in the US? How about the use of their associated drugs? Do we need to study all this stuff as exhaustively as we do our allopathic treatments? Or do we give them a break and let quaint little traditions continue? … like we are running little curiosity shoppes in Disneyland? Do you believe any treatment, if truly believed and trusted by the patient, is as good as an effective placebo? Couldn’t we eliminate all kinds of testing and trials if we simply got our patients to believe all our treatments were going to work? Maybe we could hypnotize patients and do anything we wanted as long as they Believed?

I don’t know the answers here. But we do need to pay attention as we don’t want to detach science from medicine too much. Mankind deserves to gradually move ahead scientifically. We are worth this. And if practices get too retrograde or quaint we probably do need to pull them forward a bit into modernity. I don’t want to be anal about standardization either.