By KEN TERRY

(This is the fifth in a series of excerpts from Terry’s new book, Physician-Led Healthcare Reform: a New Approach to Medicare for All, published by the American Association for Physician Leadership.)

Real healthcare reform depends on an effective plan to reduce cost growth. To achieve this goal, it makes a whole lot more sense to cut waste than to limit access to necessary services or slash provider payments to the bone, noted Donald Berwick, MD, a former acting CMS administrator, and Andrew D. Hackbarth, a RAND Corp. researcher, in a 2012 JAMA article. In their telling, a significant reduction in waste would allow us to bend the cost curve without hurting healthcare quality or access.

Berwick shared with me that he doesn’t know how much unnecessary care physicians or hospitals could safely eliminate. “Some of it is marbled into the daily activities of healthcare organizations,” he said. “There would have to be systemic changes to get it done. But it’s a matter of will. With enough will, a lot of it could be eliminated. And when you’re talking about $1 trillion [worth of waste], even if you get 10% of it, that’s a tremendous amount that could be applied to other activities.”

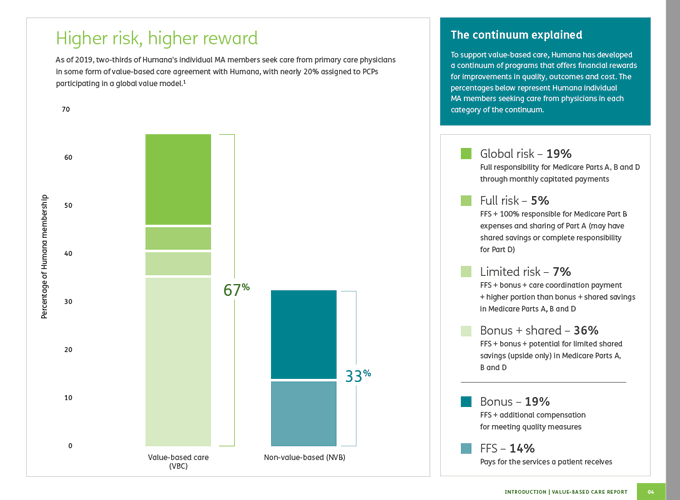

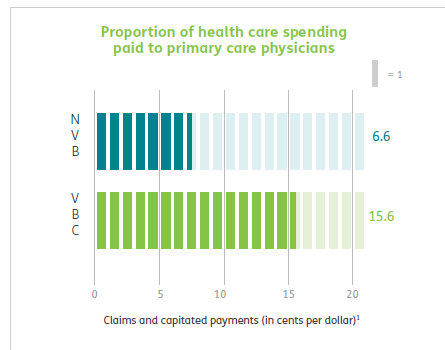

Risk-based contracts, whether shared savings or capitation, can incentivize physicians to reduce waste. From the viewpoint of long-suffering primary care physicians, value-based-care agreements that let them share in the savings they generate are a godsend. Of course, not all primary care doctors are willing to take financial risk or change their practice patterns. But if maintaining their current income depends on it, most physicians will embrace change.

Specialists, too, can benefit by embracing the new paradigm. If they’re mainly being paid fee for service, they’ll have to forgo a lot of lucrative tests and procedures. But they can still keep their incomes up by delivering more-appropriate procedures and tests to a larger patient population.

Continue reading…