In an age where big data is king and doctors are urged to treat populations, the journey of one man still has much to tell us. This is a tale of a man named Joe.

In an age where big data is king and doctors are urged to treat populations, the journey of one man still has much to tell us. This is a tale of a man named Joe.

Joseph Carrigan was a bear of a man – though his wife would say he was more teddy than bear. He loved guitar playing, and camp horror movies. Those who knew him well said he had a kind heart, a quick wit and loved cats.

I knew none of these things when I met Joe in the Emergency Department on a Sunday afternoon. I had been called because of an abnormal electrocardiogram – the ER team was worried he could be having a heart attack. Not able to make sense of the story on the phone, I was in to try to sort it out. Joe was gruff, short with his answers – but clearly something just wasn’t right. He was only 54 but had more problems than the average 50 year old. Progressive calcification of his aortic valve some years ago had caused intolerable shortness of breath resulting in replacement with an artificial valve. Longstanding diabetes had resulted in kidney failure and dialysis, and most recently abnormal liver tests had revealed the presence of the early stages of cirrhosis from hepatitis C. Yet Joe continued to live an active life – with only a tight circle of family and friends aware of the illnesses beneath the surface.

But on this particular day it was readily apparent Joe was not well. It didn’t take long to figure out that Joe had an infection somewhere. He had come in feeling hot at times, but having chills at others. Review of his ECG, stored telemetry in the ER revealed a conduction disturbance not infrequently seen called a left bundle branch block, as well as a rhythm disturbance called atrial fibrillation , but no evidence of a heart attack that had prompted the ER to call me. I told Joe and is anxious wife that he needed to be admitted to the hospital to find where the infection may be coming from.

Joe had a number of places he could be harboring an infection. While dialysis maybe one of the modern marvels of the world, the concept is fairly crude. In the absence of functioning kidneys an artificial machine does the work of the kidneys. Via large catheters the patient’s blood is removed, circulated through the machine and then returned to the patient. The flow required to circulate enough blood over a course of three hours involves creation of large conduits between arteries and veins, or placement of artificial grafts. Every access of these vessels with dialysis sessions carries a risk of introducing bacteria into the bloodstream, making infections a common event in this population. Complicating matters further, Joe had an artificial heart valve, which lacking the natural immunity of native heart valves, are especially prone to seeding by bacteria.

I told the admitting team that if no other source of infection became immediately obvious he would need an ultrasound to more closely examine his valve. That night I was called by the overnight resident in the hospital because Joe had a low heart rate. He felt fine, and his blood pressure was OK . I stopped a heart rate lowering medication that he had been on hoping this may be the cause. The next morning a review of his electrocardiogram and recorded telemetry demonstrated an ominous finding – episodic heart block. The heart’s four chambers are segregated into two small upper chambers that contain the pacemaker function of the heart and two lower chambers that are the powerful mechanical pumps which circulate blood. The upper chambers are electrically insulated from the lower chambers except for narrow specialized bundles of tissue that function as electrical cables. The specialized conduction fibers form an intricate lattice that allows the normal heart to contract in less than 100 ms. The weak point is a narrow isthmus in close proximity to the aortic valve that the electrical bundles must navigate near their origin. In Joe’s case, the electrical bundles were conducting in a stuttering fashion because bacteria was eating away at precious cardiac tissue surrounding the artificial valve.

There is only one treatment for this: surgery. John needed a surgeon to open his chest, take out his infected aortic valve, wash out the abscess and put another valve in its place .

I called the surgery team immediately – Joe was clearly a high risk case. The presence of kidney disease, liver disease, and prior open heart surgery were all independently high-risk markers. Joe of course had all three. Yet, he was an active functional 54-year-old. What was the other option? Let him die? My initial conversation with the surgeon was a positive one, and surgery was scheduled for the following day.

The following day brought a decidedly different tone. There was a brief discussion about a conversation with the hepatology team having changed the surgeon’s mind. A prediction score for patients with liver disease suggested there was a 50% chance he would be dead in 6 months regardless of his current life threatening cardiac abscess. That score seemed to be an overestimate, and hepatitis C is now a treatable illness but regardless, I pushed back and responded that the chances he would be dead in 2 weeks with his current condition was 100%. After some more parrying back and forth – the real reason for the cold feet emerged. Outcomes of cardiac surgery are publicly reported for all institutions and surgeons nationally, and in the state of Pennsylvania. After discussing the case with the other surgeons at the institution, the decision at this hospital had been made: Joe had too high a chance of making the institution look bad.

How did we get here?

Public reporting

The desire for public reporting arises from an attempt to broadcast value to a public eager for information. The Institute of Medicine’s seminal report in 1999 suggesting 98,000 patients die due to preventable medical errors every year added a sense of urgency and necessity to the push to grade providers.

Public reporting actually began more than thirty years ago – in 1984 – when the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), now known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), began to publicly report the hospital mortality rates of Medicare patients. The agency identified 269 hospitals that were outliers with regards to death rates. Although the analysis attempted to control for a variety of risk factors, it was heavily criticized and eventually HCFA stopped publishing the data.

There was no turning back though. New York state and Pennsylvania followed suit and started publicly reporting cardiac surgery outcomes. The group in charge of reporting in Pennsylvania was the Pennsylvania Health Care Council (PHC4) -created by the Pennsylvania General Assembly with the charge of improving the quality of care and restraining health care costs.

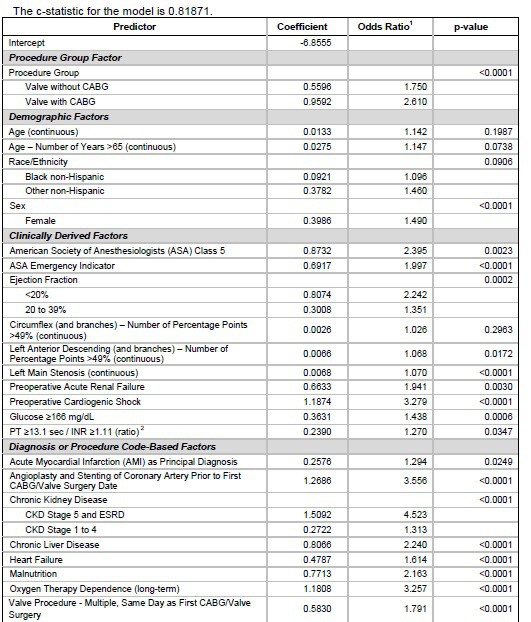

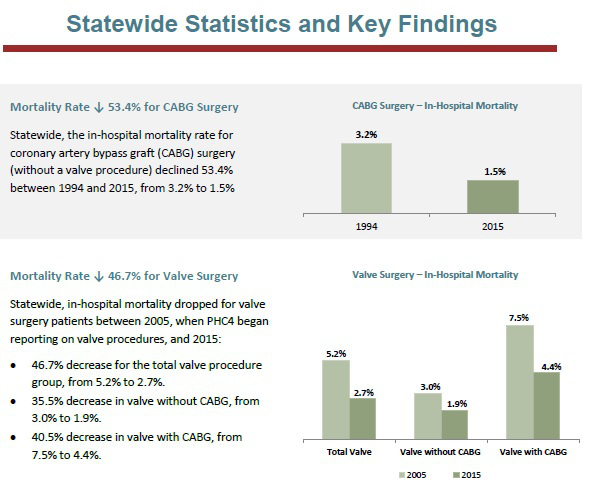

As the HCFA learned, reporting outcomes is a complicated business. Reporting outcomes relies heavily on the ability to risk stratify patients. The PHC4 struck on what is now a common model – calculate the expected mortality of each patient based on who they are and how they present and compare this to the actual reported mortality. A number of factors are considered, and each factor is weighted with regards to its impact on mortality with surgery.

Figure 1 Clinical Predictor data table, Calculating expected mortality

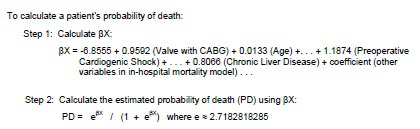

The final data is then presented for the public’s perusal in an easy to understand table with actual and expected mortality for every hospital and surgeon in Pennsylvania.

The figure below demonstrates the results of three large hospital systems in the Philadelphia region.

Figure 2 . Observed/Expected Hospital mortality

Teaching to the test

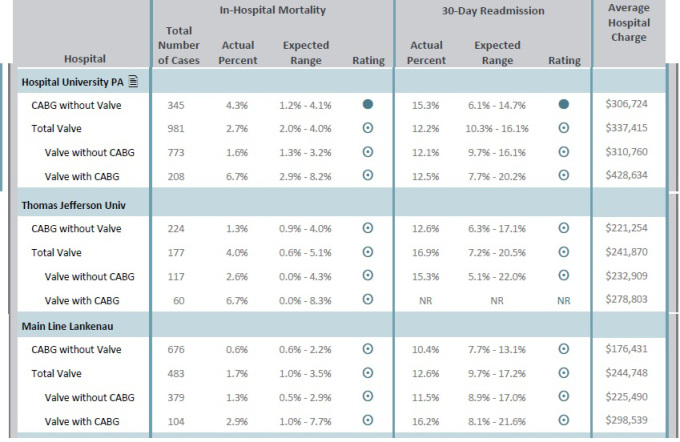

Proponents of public reporting will point to improved outcomes in the era of public reporting. In Pennsylvania, for instance, hospital mortality for Bypass (CABG) surgery dropped from 3.2% to 1.5%, and for Valve surgery dropped from 5.2% to 2.7%.

Figure 3. Cardiac surgery in-hospital mortality

Figure 3. Cardiac surgery in-hospital mortality

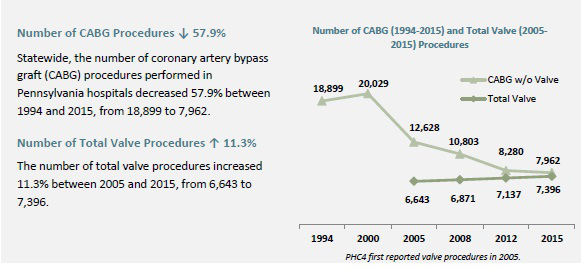

The only thing more impressive than this is the drop in bypass procedures done statewide between 2000 and 2015 – which reflects an almost 60% drop from 20,029 procedures to 7,962 procedures.

Figure 4. Volume of cardiac surgery

Figure 4. Volume of cardiac surgery

An optimistic conclusion to draw from the data is that there are fewer unnecessary procedures being performed and those that are being done are of higher quality in a safer environment. The more troubling explanation is that surgeons are operating less, and improved mortality relates to avoiding high risk patients.

I spoke to a cardiac surgeon who had practiced in the public reporting era in New York State to ascertain his thoughts. He told me that “without a doubt” this was a consideration that impacted who he and his colleagues would take to the operating room. He spoke of how surgeon’s would “play the game” to improve their numbers by not necessarily denying the sickest patient, but rather waiting them out. He gave me an example.

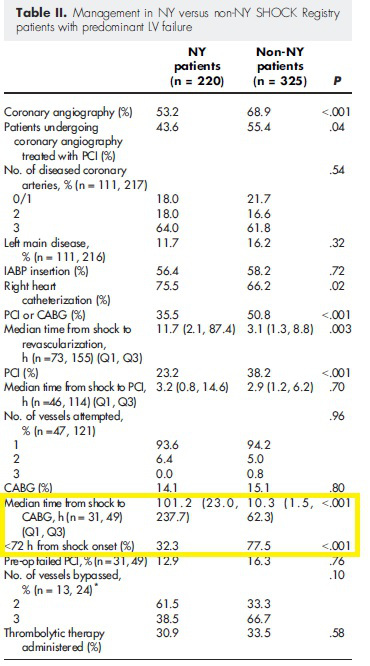

One of the stronger clinical predictors that impacted expected mortality was cardiogenic shock. Cardiogenic shock refers to patients who suffer a heart attack so severe that their entire cardiac function is compromised to the point that the heart is unable to deliver an adequate amount of blood flow to vital organs such as the kidney, liver and brain. A common approach by surgeons was to place these patients in the cardiac critical care unit or transfer the patient – the patients that survived a week were offered surgery. The cold calculus makes sense – the expected mortality of the patient continued to be high as the patients were still labeled as cardiogenic shock – but clearly waiting allowed selection of a lower risk group of patients.

I despaired after hearing this about finding published data to support what I had heard, as I frequently find datasets simply aren’t granular enough to represent clinical practice. In this particular case I was rescued by the SHOCK registry that compared patients presenting in cardiogenic shock in NY patients and Non-NY patients.

Figure 5. Differences in treatment of Cardiogenic shock patients in NY and nonNY patients

The results are stunning. As highlighted in the above table – the time to cardiac surgery in patients presenting with a heart attack and shock in New York State was different by almost 4 days!

The footprint of risk aversion is found even in the published data supportive of public reporting. Peterson et. al, found declining CABG mortality in NY state with no apparent decrease in access, but troublingly, could not elucidate a mechanism for the decline in mortality. If the point of profiling hospitals and surgeons as good or bad was to direct more patients to high performing centers, NY state officials found no evidence of migration of patients from high to low mortality hospitals.

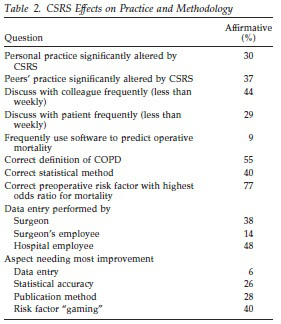

Surveys of cardiac surgeons bear out that enmasse, public reporting has markedly altered practice based on public reporting primarily by denying patients surgery.

Figure 6. Cardiac surgery survey results of public reporting

It used to be that a decision on surgery was between surgeon and patient. Risks were outlined, and a decision arrived at. The patient and doctor were in it together. Surgeons operated on high risk patients as long as they felt comfortable the patient and family understood the risks. This construct exists no more. Especially in an era where surgeons are employed by health care systems, the surgeon is now beholden to masters that never step into hospital rooms. Surgeons with high mortality rates that make the institution look bad face serious repercussions, and even worse, put future employability at risk. Shared decision making is a joke – not because decision making isn’t shared but because the shared decision is between surgeon, risk score, and hospital system – the sickest patients don’t have a choice anymore.

Back to Joe

And so it was with Joe. Faced with certain death, he wanted to live, but I could not find a surgeon at my institution to operate on him. The hyperefficient health care system moved quickly in this case. The plan from the CCU team was now hospice/palliative care. I couldn’t stomach it. I told Joe that I was going to find a surgeon who would give him a shot. So I called a center that did the most valve surgeries in the city. This wasn’t the first time in my years in practice that a patient of mine had been turned down by a surgeon at a local institution. Smaller volume centers are even more susceptible to risk aversion because their smaller volume amplifies the effects of bad outcomes. The largest center in the city had bailed my patients out before from this predicament.

This time was different. Unbeknownst to me, the academic nationally renowned busiest center in the city had been taken to task in the just published Pennsylvania public report because they had been found to have worse than expected mortality. The expected mortality was 1.2% – 4.1%, and the observed mortality was 4.3%. Of 345 patients who underwent bypass surgery 15 died – one fewer death would have put the center in the expected range. To rub salt in the wound, the local paper ran a story on the report and quoted a competing health system’s surgeon as noting the difference could relate to a minimally invasive surgery they did more of. Not mentioned was the fact that the smaller competing health system routinely sent their sickest, most complex patients to the larger academic center.

So, the answer again was no. Undeterred, I called Johns Hopkins next. The cardiac surgeon patiently listened to my story – and inquired why no hospital in the city would operate on him. I told him about public reporting, and he in turn told me about Maryland’s global payment system. Maryland hospitals were not paid per admission anymore, they were paid a per capita amount related to the number of patients attributed to them. The positives are that hospitals are incentivized to set up systems to keep patients out of hospitals. The downside is that they have a powerful disincentive to take on a complicated high risk out of state patient like Joe. I was told bluntly that Maryland was not paying for this.

I discussed the case with a prominent cardiothoracic surgeon who said explicitly –

“Politically impossible to do this case… Honestly, the big picture: he is a casualty of the public reporting system we have in the US and Pennsylvania where risk aversion is always with us. It’s kind of sad. There are consequences to all the decisions society makes”

Consequences. Trade-offs. This is decidedly not what the public hears. The public hears things like the ‘triple aim’ – improve patient experiences of care, improve the health of populations, and reduce the per capita cost of health care. You can have your cake.. and eat it too! But there is a cost to all this, and it is a cost borne by our sickest, most vulnerable patients.

When CMS announced a policy in 2006 that attempted to restrict coverage of weight loss surgery to centers of excellence (COE), a study noted the unintended consequence of trying to make the surgery safer was a reduction in the proportion of minority patients receiving the surgery. I imagine that had Joe been on the board of trustees of the hospital he would have a different set of options.

Figure 7. Proportion of minority patients offered bariatric surgery

There are so few of these patients relative to the total that they won’t move the needle when it comes to numbers population health devotees care about like life expectancy and overall cardiac mortality. But the impact of this culture shift extends beyond the smattering of patients affected.

America has long been the envy of the world when it came to innovative surgical techniques. The landscape for much of American history has consisted of brash physicians willing to push the envelope in dying patients with impossible odds. Bennie Solis was one such 3 year old dying of an irreversible liver disease when he was operated on by Thomas Starzl in 1963. Starzl thought he had perfected the technique of transplantation in dogs before attempting the feat – but he was wrong. Bennie bled to death on the operating table, his damaged liver no longer able to make substances that would clot blood. Starzl and the surgical team were devastated, but the lessons learned with Bennie’s death increased the chances of success for the patients that followed. This is true of the history of every new surgical procedure attempted. Innovation requires risk taking not risk aversion. It is difficult to imagine a man like Starzl taking on the sickest of the sick patients at Johns Hopkins today.

The sad part is that the age of penury driving this behavior is one where overall health care spending continues to accelerate to the tune of 3 trillion dollars annually. Our health care overlords may save some dollars on Joe, but won’t blink when spending billions of dollars on health care accountants, data entry clerks, hospital coding specialists, and any number of low yield primary care preventions geared to the worried well.

Some think the solution is simply better risk adjusting, or exclusions for centers performing at the frontiers. Perhaps. Or throw the whole system out and focus on the rotten apples among us. I don’t know. I do know that however well intentioned the practice of public reporting may be, the consequences may be severe.

I couldn’t find a surgeon who would operate on Joe. So he died.

He never made it home to play his guitar.

The pictures and the story are presented with the permission of Joe’s wife, Debra. Ever gracious, she hoped his story would teach us something.

Here’s hoping it will.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist in Philadelphia. He can be found on twitter @anish_koka

Categories: Uncategorized

Outcome reporting is a two edged sword and the patient got sliced by the side many believe is a dull edge.

Socialized medicine leads to this exact problem in just a slightly different fashion. Saving and the distribution of dollars becomes King. Suddenly it is business people and managers that call the shots. That is what has been happening as government regulates forcing physicians to work for consolidated businesses and hospitals that pull the strings based upon the evaluation of a CFO instead of an M.D..

Risk adjustment is great, but we are very bad at it and it can be gamed.

You say, ”I would favor trusting the pt and physician make these tough calls unfettered by allegiances to other masters. The beauty of America has been this very ability to offer everyone from the homeless man to the board member the same level of care – we are slowly losing that – and I’m not sure it has to be this way given what we still can and do spend on healthcare overall.” I wholeheartedly agree.

Some don’t recognize that perfection is the enemy of good.

Thanks for a wonderful article.

It is so sad! I had a numbers related experience. A heart surgeon was more worried about his numbers than letting a family member go peacefully after complications from a heart valve replacement surgery. She ended up with an ischemic dead bowel, most everything removed and a colostomy. While in tremendous pain, he allowed her to suffer without pain control and sedation while on the vent. Her tongue nearly split in half from the endotracheal tube. She was a golden yellow from the liver failure related to poor profusion. She wanted to die. For 30 days post cardiac surgery, the surgeon refused to make her DNR as she requested. Day 31, he finally offers palliative care. The really, really sad part….she had only wanted the surgery so she could walk to her mailbox without getting short of breath. That jerk of a surgeon insured she suffered tremendously to keep her alive withering in pain just to avoid a hit to his 30 day mortality rate.

50% may be a low estimate on the part of the GI docs. Guy is awfully young to be having a redo valve. Why was it replaced initially?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4793506/

Good writing, Anish. Thank you.

This seems one of those problems for which there is no facile answer.1. It’s good to have public reporting and 2. public reporting has bad side effects.

Backing away can give us different frames:

If we had a single payer would public reporting still be useful? (as competition and market share are not particularly relevant here.)

Highly accurate risk adjustment sounds helpful but details could obstruct patient understanding…how far to go in this effort?

Is purpose of public reporting to enhance smart shopping by patient or referring physician? Is there evidence this is happening?

Is purpose to improve provider performance?, save money? Evidence?

Is purpose to remove bad providers? Evidence?

Is public reporting fair to the few subsets of professionals who are singled out? Congress, lawyers, airline pilots, teachers, ad infinitum, are potential subjects for this too.

Is all this record keeping and publicity costing more than the benefit of enhancing provider skill? ..,or whatever we are doing this for.

Its a fallacy to assume that no progress would have occurred without the checklist movement.. The idea of sterile procedure somehow took hold and spread well before there were ACOs. I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t hold doctors and health systems responsible – i’m suggesting the way we’re going about it is mindless. http://www.philly.com/philly/blogs/healthcare/Medical-Errors-The-problem-with-getting-to-zero.html

Good point Matthew. There is a case to be made for rationing.

By all means use data to understand what’s happening, identify safety issues and flag problem doctors. But when you use this kind of reporting data as the underlying unit of knowledge to organize your healthcare system you run into a problem. All data is political.

Fundamentally, this isn’t an accounting problem.

This is a political problem.

And a human problem.

Anish, Princeton’s Uwe Reinhardt wrote in the past that healthcare quality can be defined and summarized by the acronym, POSS. P is for process — following evidence based guidelines and protocols. O is for outcomes, ideally risk-adjusted. The first S is for patient safety — minimizing hospital acquired infections, etc. The second S is for patient satisfaction which can include non-medical criteria like good food, flat screen televisions, valet parking and pleasant nurses. These four criteria would have to be weighted in some appropriate way with outcomes presumably the most important to patients. The risk-adjustment state of the art apparently isn’t where it needs to be yet.

As for the quality / accountability movement, hasn’t there been a meaningful decline in central line and VAP infections and haven’t the use of checklists and timeouts in the OR reduced egregious errors like wrong-site surgery?

As u know, I’m a skeptic of the emerging quality/accountability movement. Quality is measured at the moment by checking a box on the EHR that says I prescribed a statin and performed a depression screen..

Perhaps we should take a hiatus until we can appropriately risk adjust. Why did we even embark on this if we weren’t sureness we could risk adjust?

Who decides what’s reasonable? In this case patient, surgeon, and cardiologist thought it reasonable. Blalock thought it was a reasonable thing to operate on babies who were born blue that were ‘destined’ to die. Worth pointing out that there were a class of folks at the time that thought this was a waste of resources and unethical.

The ability we traditionally have had to offer the best therapy equally to rich and poor is what has made American healthcare

special.

Im an advocate for making patients responsible for the health care equivalent of oil changes- not for catastrophic illnesses.

I keep reading that in other countries, doctors are quicker to say I’m sorry but there is nothing more we can do than they are here. Patients in other countries, for their part, are less likely to impose unreasonable costs and expectations on their fellow citizens because that mentality is expected as part of the culture around the social safety net in those countries.

In the U.S., the prevailing mentality among most patients is I want what I want when I want it and I expect someone else to pay for it. I think there is a legitimate role for QALY metrics to help payers decide what they will and won’t cover and pay for. Of course, if you can self-pay and can find a doctor to take your longshot case, go for it if you want to.

“there’s strong evidence that the role of public reporting in today’s emerging accountability/quality improvement systems is important”

I’m sure I’m not the only one who hasn’t seen that evidence. Please share.

So Stephen Fiehler is making the point I was trying to make in the comment below. At some point in health care (whether in surgery, chemo therapy, et al) we need ACCURATE data on which to say, “it isn’t worth spending $X00,000 for a potential few more days/weeks/years of life, especially if at a massively reduced level of health/happiness”. No-one of course wants to really have that conversation BUT a $ spent by the medical industrial complex is a $ not spent on early childhood education, parks, healthy food for kids and bunch of other stuff that may have greater net utility. So if we are going to ration — AND WE DO ALL THE TIME ALREADY — let’s do it in a rational way.

The solution to unnecessary surgeries is not to deny those who would benefit from surgery? Should we take solace in the fact that Joe’s death was balanced by somebody else who didn’t need surgery? If you want to look for savings I’d go after the billions we spend on bean counters and innovation programs that serve as sources of employment and little else

I sense your desire to quantify this – I don’t know if it’s possible- but say some score gave said his surgery was associated with an 80% mortality – isn’t that still better than a 100% chance of dying? And as you point out the case is different if the pt is 90 and demented or if they’re 55 with end stage liver disease (Joe had mild disease d/t hep c that in 2017 can be treated)

I would favor trusting the pt and physician make these tough calls unfettered by allegiances to other masters. The beauty of America has been this very ability to offer everyone from the homeless man to the board member the same level of care – we are slowly losing that – and I’m not sure it has to be this way given what we still can and do spend on healthcare overall.

If you’re a Powerpoint, everything looks like a presentation.

“There may be situations in which an additional 6 months for someone with debilitating SOB and other problems aren’t worth ~$300,000 of taxpayer money”

Um. Wouldn’t most people call this rationing?

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Surgeons are trained to perform surgery. For every story like Joe’s, there are many surgeries and procedures performed that should not have been. Our country is now $20 trillion in debt. We spend over $1 trillion per year on Medicare and Medicaid. If we don’t start controlling our healthcare spending, it won’t be long before we’re $30 trillion in debt. There may be situations in which an additional 6 months for someone with debilitating SOB and other problems aren’t worth ~$300,000 of taxpayer money or additional claims that increase everyone else’s premiums.

Wonderful piece. I agree with Adrian Gropper that we need much better risk adjusted reporting. Just as we need better risk adjusted payment in Medicare Advantage. Both systems now lead to unintended consequences.

I do have a minor and a major question. First, Anish states that there was a “drop in bypass procedures done statewide between 2000 and 2015 – which reflects an almost 60% drop from 20,029 procedures to 7,962 procedures” presumably most of that was a replacement of bypasses with stents instead? Is there any data on total cardiac procedures, or any attempt to tease out which CABGs weren’t done due to the “transparency” issue.

Second, while there was an estimate that the patient Joe had only a 50% chance of living 6 more months irrespective of the surgery, can we estimate what his chances of making it through the operation and the immediate recovery period were? I know it’s an imprecise science, but if we could do that, then we could convert surgery into a kind of baseball cybermetrics where surgeons don’t get knocked on overall mortality but instead deaths vs expected deaths (e.g equivalent of the WOR stat in baseball).

If we can do that then we can have a serious discussion about both what Joe the patient and his family wanted, what his likely outcome was, and whether society/taxpayer/employer/insurer/etc should be paying for that likely outcome (if it wasn’t going to change much overall). It may well be that this would be different for a 54 year old than for say a 95 yr old with dementia. Speaking as a 54 year old I hope so! but that is a serious discussion.

It sounds like Joe was denied surgery and left to die based on a faulty data collection process, and no one can defend that.

Excellent piece Anish, but my conclusion is not about public reporting but rather about inadequate risk adjustment in public reporting. The risk adjustment fails at both the institutional and the individual surgeon level and in multiple ways. There’s no way to capture the essence of your professional opinion (or the family’s) in this particular example as part of the risk adjustment. Once we understand that problem, we can begin to fix it.

Anish — excellent piece with magnificent detail. As a long-time advocate of public reporting, I’m of course aware of the “risk aversion/avoidance–bad outcomes” problem. It has bedeviled the field for many years, and the danger of it become institutionalized is significant. This piece puts a well-deserved, thoughtful and poignant spotlight on the problem.

That said, we can’t let the problem/challenge of risk avoidance scuttle meaningful public reporting. As you know there’s strong evidence that the role of public reporting in today’s emerging accountability/quality improvement systems is important. Not to mention that the public deserves to know.

As Barry Carol says below: “It wouldn’t matter if he had the best gold-plated health insurance that money could buy or even if he were mega-wealthy and was prepared to pay out-of-pocket.” There are serious ethical questions raised for the surgeons who refused to take the case. If Barry is right, this could happen to any of us and we would not know the surgeons’ recommendations were not based on our interests, but their own.

At some point the (mainly European) acronym QALY, quality adjusted life year, will have to face consideration. And to Barry Carol’s point, Wikipedia links several cost-related discussions. The Wikipedia article opens with this:

“The quality-adjusted life year or quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) is a generic measure of disease burden, including both the quality and the quantity of life lived. It is used in economic evaluation to assess the value for money of medical interventions. One QALY equates to one year in perfect health. If an individual’s health is below this maximum, QALYs are accrued at a rate of less than 1 per year. To be dead is associated with 0 QALYs. QALYs can be used to inform personal decisions, to evaluate programs, and to set priorities for future programs.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quality-adjusted_life_year

Off course this content should in any good health mag. Many of readers just love it.

The specialty hospitals are driven by their tactics to maintain market share, eventually involving the process associated with referral patterns. Over-time, the high risk referral patterns can secondarily become skewed. In effect, the commitment to trigger the holy grail of “patient choice” indirectly limits the patient’s choice for the health care of high-risk needs. Either way, the result is rationing albeit indirect.

I don’t think the story Anish describes has anything to do with rationing. Instead, it has everything to do with statistics and perceived reputation. As Anish notes, these surgeons and the hospitals they work for or are affiliated with viewed Joe as too risky to operate on given his history and current cardiac and non-cardiac medical issues. It wouldn’t matter if he had the best gold-plated health insurance that money could buy or even if he were mega-wealthy and was prepared to pay out-of-pocket. The surgeons and the hospital didn’t want to risk operating on him because they feared a bad outcome that would make them look bad.

I don’t know how good the risk scoring state of the art is or to what extent it could be improved. If only a very small percentage of patients fall into an ultra high risk category, perhaps they could be treated as a separate group that wouldn’t be part of any given surgeon’s stats but would be part of the hospital’s stats separate and apart from low and moderate risk patient outcome statistics. After all, aren’t there OBGYN practices that specialize in high risk pregnancies? Why are those docs willing to take on high risk cases?

Another tragic case study of something I have complained about for years — RATIONING BY AFFORDABILITY. In the case of “public reporting” the word “affordability” is about tight control over tax money (you gotta have enough left over for executive compensation packages, investor ROI, expensive ads for Rx drugs, etc. you know). But after everything else is blown off, it’s about money and rationing.

Here’s my usual copy/paste screed:

Healthcare in America is like virtually everything else — housing, transportation, education, nutrition, employment — RATIONING BY AFFORDABILITY.

* Those with access to the most resources (usually money, but also education, family background, generational wealth, much more) will receive the best,

* those with less settle for less,

* those with the least get least of all, and

* anyone certifiably destitute and/or incapacitated must rely on what passes for a “safety net.”

That safety net consists of a ragged combination of public and private resources (taxes and tax-deductible contributions), old-fashioned charity (expecting nothing in return) and occasional unexpected windfalls (lottery winnings, surprise inheritance, shares of class-action legal settlements).

DENTAL CARE provides a good illustration. Top-drawer benefits include (in addition to a lifetime of routine visits) corrective procedures (over/underbite, braces, retainers, implants, cosmetic correctives, root canals & crowns) and lately access to 3-D implant creations while you wait. Those with less settle for “just the basics” which may include everyday fillings, extractions and dentures. Further down are the population who only go to a dentist when there is a problem — usually a conspicuous decayed place or toothache. And at the bottom are dental emergencies that report to hospital ED, disparately seeking pain relief. (This is one of several root causes of the opioid epidemic as people in pain shop black-market pain remedies.)

Bottom line: American dental are is why a fourth of Medicare-age beneficiaries no longer have any of their natural teeth.

Having followed this discussion for the last ten or fifteen years, I don’t expect lay people to do much more than read the headlines and hope for the best. Those who are curious would do well to look at how healthcare is managed (or not) in other countries. Short version: single-payer plus private insurance with wage and price controls that most Americans consider a pathway to tyranny.

The era of onerous rationing has arrived, personified by this story. Given the history, I wonder how his diabetic health care, at onset, was organized: diligence with diet & testing or just a prescription called in every 6 months. Was he followed every 3 months or “once in awhile” for his blood pressure? Did he have any dental care?

.

I cannot imagine the angst associated with this person’s final days. In spite of the larger picture, it is hard to imagine that Anish could continue his commitment to spontaneously generate trust, collaboration and reciprocity (Social capital) for solving the social dilemmas that occur daily for many citizens within the civil life of healthcare.

Tx for the kind words Paul!

Barry, we could always do better. There are bad doctors that operate freely. Our professional societies are lax. In general, I think there’s a good matches driven by referring doctors- but nothing is perfect. The public and you want perfection- not sure that’s achievable and the pursuit of such May cause the system to regress rather than progress

This is indeed a powerful story and a classic illustration of unintended consequences…If I’m a patient like Joe, though, what alternative mechanism do I have to identify and avoid the “bad apples” if I don’t have a knowledgeable doctor or nurse in my family or among my circle of friends? Doctors, like most professionals, have a strong bias toward protecting their own and the record of removing the small number of lousy doctors from practicing medicine is less than stellar to put it mildly. Ideally, there would be a good, professional, objective referral center that could help to steer patients toward high quality doctors rather than just give them a list of names without comment but even that may not be of much use for a patient who lands in the ER and needs surgery immediately.

What would be helpful, in my opinion, is for the profession to do a better job of weeding out the small number of bad doctors. Too often, I think, the mentality of the committee members charged with making such decisions is (1) there but for the grace of God go I, (2) he probably has a mortgage and a family to support so (3) let’s not take away his livelihood.. That attitude certainly helps the doc. The patient, not so much.

Anish, This is a powerful and disturbing story!….and deserves wide distribution. With a little editing it ought to be submitted to the Wall Street Journal op-ed page…..or Washington Post or NY Times.