So in this week of THCB’s 20th birthday it’s a little ironic that we are running what is almost a mea culpa article from Jeff Goldsmith. I first heard Jeff speak in 1995 (I think!) at the now defunct UMGA meeting, where he explained how he felt virtual vertical integration was the best future for health care. Nearly 30 years on he has some reflections. If you want to read a longer version of this piece, it’s here—Matthew Holt

By JEFF GOLDSMITH

The concept of vertical integration has recently resurfaced in healthcare both as a solution to maturing demand for healthcare organizations’ traditional products and as a vehicle for ambitious outsiders to “disrupt” care delivery. Vertical integration is a strategy which emerged in US in the 19th Century industrial economy. It relied upon achieving economies of scale and co-ordination through managing the industrial value chain. We are now in a post-industrial age, where economies of scale are in scarce supply. Health enterprises that are pursuing vertical integration need to change course. If you look and feel like Sears or General Motors, you may well end up like them. This essay outlines reasons for believing that vertical integration is a strategic dead end and what actions healthcare leaders need to take.

Where Did Vertical Integration Come From?

The strategy of vertical integration was a creature of the US industrial Revolution. The concept was elucidated by the late Alfred DuPont Chandler, Jr. of the Harvard Business School. Chandler found a common pattern of growth and adaptation of 70 large US industrial firms. He looked in detail at four firms that came to dominate markedly different sectors of the US economy: DuPont, General Motors, Sears Roebuck and Standard Oil of New Jersey. They all followed a common pattern: after growing horizontally through merging with like firms, they vertically integrated by acquiring firms that supplied them raw materials or intermediate products or who distributed the finished products to final customers. Vertical integration enabled firms to own and co-ordinate the entire value chain, squeezing out middlemens’ profits.

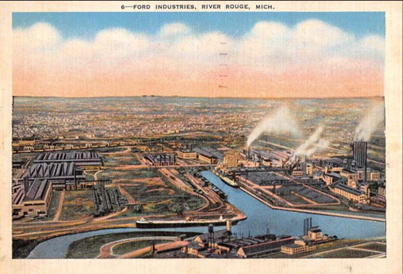

The most famous example of vertical integration was the famed 1200 acre River Rouge complex at Ford in Detroit, where literally iron ore to make steel, copper to make wiring and sand to make windshields went in one end of the plant and finished automobiles rolled out the other end. Only the tires, made in nearby Akron Ohio, were manufactured elsewhere. Ford owned 700 thousand acres of forest, iron and limestone mines in the Mesabi range, and built a fleet of ore boats to bring the ore and other raw materials down to Detroit to be made into cars.

Subsequent stages of industrial evolution required two cycles of re-organization to achieve greater cost discipline and control, as well as diversification into related products and geographical markets. Industrial firms that did not follow this pattern either failed or were acquired. But Chandler also showed that the benefits of each stage of evolution were fleeting; specifically, the benefits conferred by controlling the entire value chain did not last unless companies took other actions. Those interested in this process should read Chandler’s pathbreaking book: Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the US Industrial Enterprise (1962).

By the late 1960’s, the sun was setting on the firms Chandler wrote about. Chandler’s writing coincided with an historic transition in the US economy from a manufacturing dominated industrial economy to a post-industrial economy dominated by technology and services. Supply chains re-oriented around relocating and coordinating the value-added process where it could be most efficient and profitable. Owning the entire value chain no longer made economic sense. River Rouge was designated a SuperFund site and part of it has been repurposed as a factory for Ford’s new electric F-150 Lightning truck.

Why Vertical Integration Arose in Healthcare

I met Alfred Chandler in 1976 when I was being recruited to the Harvard Business School faculty. As a result of this meeting and reading Chandler’s writing, I wrote about the relevance to healthcare of Chandler’s framework in the Harvard Business Review in 1980 and then in a 1981 book Can Hospitals Survive: The New Competitive Healthcare Market, which was, to my knowledge, the first serious discussion of vertical integration in health services.

Can Hospitals Survive correctly predicted a significant decline in inpatient hospital use (inpatient days fell 20% in the next decade!). It also argued that Chandler’s pattern of market evolution would prevail in hospital care as the market for its core product matured. However, some of the strategic advice in this book did not age well, because it focused on defending the hospital’s inpatient franchise rather than evolving toward a more agile and less costly business model. Ambulatory services, which are today almost half of hospital revenues, were viewed as precursors to hospitalization rather than the emerging care template.

Continue reading…