As the 20th Birthday rolls on I thought I’d bring out a more recent piece first published in October 2020, albeit one that relies heavily on 25 year old data to make a point. This is some evidence to back up Jeff Goldsmith’s comment on the original that for all the talk “ ‘Value based” payment is a religious movement, not a business trend’ ” By the way, Humana updated these numbers last year and there’s been basically no change — Matthew Holt

Humana is out with a report saying that its Medicare Advantage members who are covered by value-based care (VBC) arrangements do better and cost less than either their Medicare Advantage members who aren’t or people in regular Medicare FFS. To us wonks this is motherhood, apple pie, etc, particularly as proportionately Humana is the insurer that relies the most on Medicare Advantage for its business and has one of the larger publicity machines behind its innovation group. Not to mention Humana has decent slugs of ownership of at-home doctors group Heal and the now publicly-traded capitated medical group Oak Street Health.

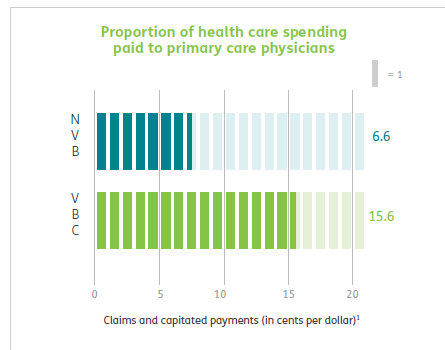

Humana has 4m Medicare advantage members with ~2/3rds of those in value-based care arrangements. The report has lots of data about how Humana makes everything better for those Medicare Advantage members and how VBC shows slightly better outcomes at a lower cost. But that wasn’t really what caught my eye. What did was their chart about how they pay their physicians/medical group

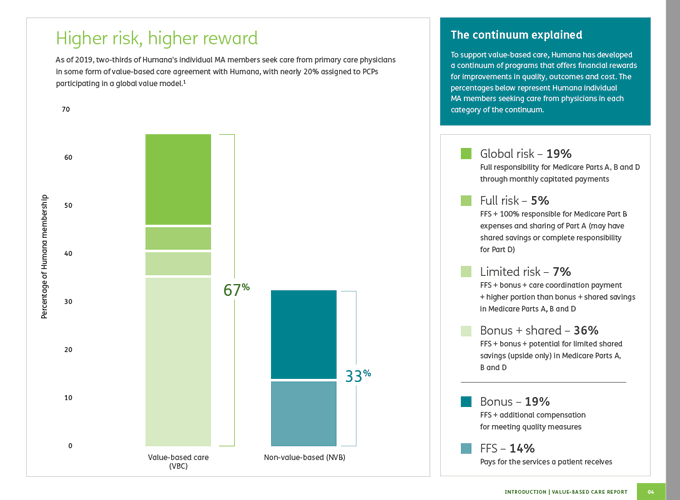

What it says on the surface is that of their Medicare Advantage members, 67% are in VBC arrangements. But that covers a wide range of different payment schemes. The 67% VBC schemes include:

- Global capitation for everything 19%

- Global cap for everything but not drugs 5%

- FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings 7%

- FFS + some share savings 36%

- FFS + some bonus 19%

- FFS only 14%

What Humana doesn’t say is how much risk the middle group is at. Those are the 7% of PCP groups being paid “FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings” and the 36% getting “FFS + some share savings.” My guess is not much. So they could have been put in the non-VBC group. But the interesting thing is the results.