By STEVEN ZECOLA

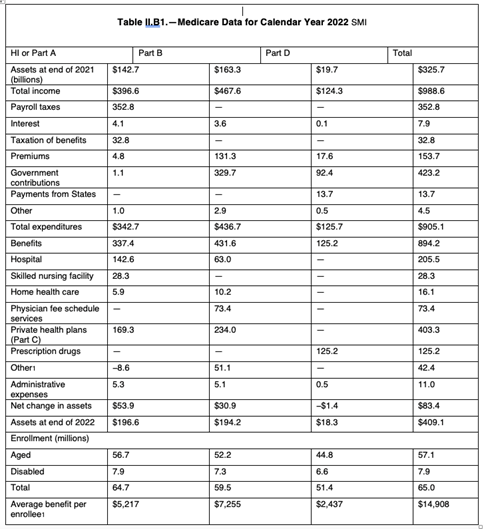

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Service (“HHS”) is responsible for a wide range of activities relating to medical and public health. It has 60,000 employees and a $1.7 trillion annual budget with approximately $140 billion for discretionary spending. For the past 13 years, HHS has been spearheading a National Plan for addressing Alzheimer’s disease – with some notable successes.

Given its resources, expertise and charter, HHS should launch a National Plan to cure Parkinson’s disease patterned after its approach on Alzheimer’s disease.

Legislation, or Not

The U.S. House of Representatives has passed H.R.2365, the National Plan to Cure Parkinson’s Disease.

The bill would establish HHS as the central point for strategic direction and coordination of PD research. It would require formation of a broad-based Advisory Panel to provide strategic advice and any on-going course corrections.

There is nothing preventing HHS from putting the structure of H.R. 2365 into effect now, and it should do so without waiting for Senate action or inaction. There is no incremental funding required to implement this National Plan, nor is any Congressional approval necessary. This approach would mark an important step towards finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease, and is well within HHS’s charter.

A Cross-Section of Policy and PD Research

For those who have studied the application of regulatory policies to Parkinson’s disease research, it does not provide a productive narrative.

Levodopa was first discovered in 1910. In 1975, after 14 years of its “miraculous” treatment of PD symptoms, the FDA approved the drug. Levodopa does not cure or delay the progression of the disease. Yet, it has remained the gold standard of treatment of PD for the past fifty years. That is not to say there has been insufficient research or inadequate FDA approvals. Rather, it’s a question of where the research dollars have been funneled. It turns out that levodopa becomes less effective over time and eventually produces uncontrolled shaking. Therefore, research dollars have been targeted toward drugs that delayed the need for levodopa or controlled its side effects.

An exception to this approach was Geron, which became a leader in embryonic stem cell research. It had raised $100 million to conduct clinical trials. However, most of that money was consumed by undertaking thousands of experiments on mice under the “guidance” of the FDA. Nevertheless, Congress saw the potential of embryonic stem cells, and passed the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act.

While Congress cheered, the Evangelical movement viewed embryonic stem cell research as barbaric and akin to murdering a human life. It didn’t matter that embryonic stem cells could not become a living being unless they were implanted in a woman’s womb, and this step wasn’t part of the research efforts. Notwithstanding, the Evangelicals convinced George W. Bush to veto the legislation, and a promising path for PD research was shut down.

More recently, the House has passed bills for a National Plan to Cure Parkinson’s in its last two sessions, but the Senate has failed to act, despite a myriad of sponsors of a bill with similar provisions.

Building Upon Lessons from the Past

In 2011, Congress passed legislation establishing a National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s disease (“NAPA”). Thirteen years later, there are many lessons to be learned from that effort that can be applied in a National Plan for PD. Of particular note, the original plan had five objectives including to “Prevent and Effectively Treat AD/ADRD by 2025”.

The first report by the Advisory Council specified that the current “level of resource commitment falls drastically short of the funding needed to accelerate the pace of research on prevention, cures, and treatments for AD”. It also recommended that the Secretary examine “[h]ow HHS uses existing authorities to reduce drug development barriers and accelerate development of new therapies” and specifically called for recommendations to “accelerate the FDA review process”.

What happened? While funding was increased substantially and hundreds of potential treatments have been identified, only two drugs have been approved by the FDA under an “accelerated” review process.

While HHS may express pride in the accomplishments from the Alzheimer’s National Plan, it should conclude that the process to get an effective treatment identified and approved takes too long. For example, the FDA provides “guidance” to researchers even before clinical trials are submitted. It also regulates the provision of genetic tests. These actions needlessly slow development and reduce innovation.

Similarly, the FDA’s regulation of Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials slows down development and does little to benefit the public interest. The FDA points to multiple ways that it has accelerated the drug approval process. But the reality is that progress from PD research has been lacking.

On the other hand, in 2019, researchers issued a report – based on real-world observations — that Terazosin resulted in a lower incidence of PD and a slower development of the disease when it did occur. Terazosin has been used for over 35 years to treat other maladies. Yet the drug underwent a 13-person Phase I trial to determine if it is safe. This phase 1 trial took several years to complete. This approach was a distraction that caused unnecessary delay and cost under the FDA’s regulatory regime.

The FDA will say that its rules do not require 3 (or more) trials nor does it mandate a particular trial design. This is disingenuous. Companies spending hundreds of millions of dollars on research cannot afford the risk of shirking the FDA’s standard procedures.

Taken as a whole, the HHS should limit the FDA’s involvement in PD research to approval of Phase 3 trials. Such an approval process will speed development and foster innovation yet maintain adequate safety controls by the FDA. Research organizations would be less constrained in developing their strategies and would be held to more responsibility for their approach to research.

A Multivariate Solution Is Likely to be Required

PD is a complex disease that has different manifestations when looked at from a genetic, diet, exercise, environmental (pesticides/pollution/solvents), vitamin, drug, electronic, radiation and possibly other perspectives. As such, a multivariate solution is likely to be required to successfully treat PD.

Such a solution will not be well accommodated by the current FDA review process, with each different combination of therapies being subjected to regulatory review and intervention. The process could drag on for decades.

HHS should recognize the need for a multivariate solution and plan accordingly, as described below.

Data Collection to Identify Multivariate Solutions

In 2010, The Michael J. Fox Foundation launched the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) to find the biological markers of Parkinson’s onset and its progression. That study led to the impressive finding of a tool that can detect pathology not only of people diagnosed with Parkinson’s, but also in individuals that are at a high risk of developing it. However, after ten years, that study has only a few thousand participants. HHS should endorse and expand the scope of that study.

The “second version” of PPMI should be an overlay study designed with the end game in mind. That is, it should produce a mapping of individual people’s PD “score” over time against all relevant explanatory variables that could possibly impact PD for each individual. Such an approach is superior for identifying multivariate solutions.

To accomplish this objective, each participant would establish and maintain a unique portal for his/her own explanatory PD variables. The portal would include a series of hard-coded entry requirements covering scores of inputs. The initial set-up could be completed in piece-part (with the availability of outside assistance) and would auto-populate with each quarterly update (allowing for input of any changes that occurred after the initial set-up). The portal would interface with the growing number of portals of individual healthcare providers and would collect the diagnostic information from those systems. Personal “meters” of this sort are now actively being deployed in the field of Alzheimer’s disease given that certain therapies and drugs have shown progress against that disease.

As the above information from participants is collected over time, artificial intelligence software would be used to identify combinations of diet, exercise, supplements, genetics, sleep habits, therapies, electronics, radiation and drugs that point towards promising results. New treatments such as those undertaken in clinical trials would be added to the participant’s portal as they as are pursued by those individuals. All of the patient’s existing drugs would be analyzed in the context of all other relevant explanatory variables for that participant – over time.

As importantly, a comparative, quantifiable measurement of PD over time for each individual is required. The PPMI was originally focused on identifying a marker for PD and therefore uses a series of qualitative questions to gauge the patient’s development of PD symptoms over time. In contrast, the emphasis for this data collection effort should shift to the explanatory variables affecting PD progression over time.

In terms of the participant’s PD score, I believe a modified version of the Fitness program currently designed for the computer game “Wii” (which provides a quantitative estimate of an adult’s age based on how that person performed on certain activities) would provide more reliable results. Each participant would provide his/her own age estimator from the computer program on a quarterly basis as well as provide any updates for the various explanatory variables.

Once this revised format is established, the HHS should establish a goal of enrolling 100,000 PD participants into the study within two years.

A Better Approach for PD Research Is Available Now

HHS can – on its own accord – dramatically improve the efficiency and effectiveness of Parkinson’s research by: 1) adopting the industry-wide structure it utilized for Alzheimer’s disease, 2) embracing and expanding upon the current PPMI study and 3) limiting the FDA’s involvement in research to the approval of Phase 3 clinical trials.

Steve Zecola sold his web application and hosting business when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease twenty three years ago. Since then, he has run a consulting practice, taught in graduate business school, and exercised extensively