By JEFF GOLDSMITH and IAN MORRISON

Hospital consolidation has risen to the top of the health policy stack. David Dranove and Lawton Burns argued in their recent Big Med: Megaproviders and the High Cost of Health Care in America (Univ of Chicago Press, 2021) that hospital consolidation has produced neither cost savings from “economies of scale” nor measurable quality improvements expected from better care co-ordination. As a consequence, the Biden administration has targeted the health care industry for enhanced and more vigilant anti-trust enforcement.

However, as we discussed in a 2021 posting in Health Affairs, these large, complex health enterprises played a vital role in the societal response to the once-in-a-century COVID crisis. Multi-hospital health systems were one of the only pieces of societal infrastructure that actually exceeded expectations in the COVID crisis. These systems demonstrated that they are capable of producing, rapidly and on demand, demonstrable social benefit.

Exemplary health system performance during COVID begs an important question: how do we maximize the social benefits of these complex enterprises once the stubborn foe of COVID has been vanquished? How do we think conceptually about how systems produce those benefits and how should they fully achieve their potential for the society as a whole?

Origins of Hospital Consolidation

In 1980, the US hospital industry (excluding federal, psych and rehab facilities) was a $77 billion business comprised of roughly 5,900 community hospitals. It was already significantly consolidated at that time; roughly a third of hospitals were owned or managed by health systems, perhaps a half of those by investor-owned chains. Forty years later, there were 700 fewer facilities generating about $1.2 trillion in revenues (roughly a fourfold growth in real dollar revenues since 1980), and more than 70% of hospitals were part of systems.

It is important to acknowledge here that hundreds more hospitals, many in rural health shortage areas or in inner cities, would have closed had they not been rescued by larger systems. Given that a large fraction of the hospitals that remain independent are tiny critical access facilities that are marginal candidates for mergers with larger enterprises, the bulk of hospital consolidation is likely behind us. Future consolidation is likely not to be of individual hospitals, but of smaller systems that are not certain they can remain independent.

Today’s multi-billion dollar health systems like Intermountain Healthcare, Geisinger, Penn Medicine and Sentara are far more than merely roll-ups of formerly independent hospitals. They also employ directly or indirectly more than 40% of the nation’s practicing physicians, according to the AMA Physician Practice Benchmark Survey. They have also deployed 179 provider-sponsored health plans enrolling more than 13 million people (Milliman Torch Insight, personal communication 23 Sept, 2021). They operate extensive ambulatory facilities ranging from emergency and urgent care to surgical facilities to rehabilitation and physical therapy, in addition to psychiatric and long-term care facilities and programs.

Health Systems Didn’t Just “Happen”; Federal Health Policy Actively Catalyzed their Formation

Though many in the health policy world attribute hospital consolidation and integration to empire-building and positioning relative to health insurers, federal health policy played a catalytic role in fostering hospital consolidation and integration of physician practices and health insurance. In the fifty years since the HMO Act of 1973, hospitals and other providers have been actively encouraged by federal health policy to assume economic responsibility for the total cost of care, something they cannot do as isolated single hospitals.

- Managed Competition. Under the Paul Ellwood/Alain Enthoven/Jackson Hole Group vision of managed competition, a fragmented care system comprised of individual hospitals and autonomous physicians would be replaced by a limited number of Kaiser-like capitated integrated delivery systems serving regions and competing on price (e.g. premium/PMPM). This vision of a consolidated health system assuming population risk has been the holy grail of US health policy for five full decades, embraced by Republican and Democratic policy advocates alike. For hospitals to remain independent was to risk being isolated and commoditized by larger enterprises, either insurer- or provider-sponsored. This fear of isolation resulted in waves of hospital consolidation during the late 1970s and 1980s in anticipation of a health care marketplace populated by regional integrated delivery networks.

- Clinton Health Reforms. Under the proposed Clinton reforms in the early 1990’s, hospitals would only have access to revenues through capitated health payment from the anticipated regional purchasing alliances and could contract to be paid directly if they were capable of bearing and managing population risk. Otherwise, hospitals would have become isolated subcontractors whose offerings would have been commoditized by those who accepted population-based payment. Even though the Clinton reforms faltered, a large wave of hospital mergers and integration activity in the mid-1990’s anticipated their passage.

- HITech and the ACA. In the wake of President Obama’s 2009 Hitch Act, White House technocrats actively encouraged hospitals to absorb their physicians’ practices as a vehicle for facilitating the adoption of electronic health records. Similarly, the ACA’s payment reform initiatives, particularly the centerpiece Shared Savings (ACO) Program, relied upon on the ability of health enterprises to reach and manage the care of large populations as a bridge to a fully capitated future, spurring yet another wave of hospital consolidation.

Integration of Care and Financing has Failed to Achieve Ambitious Social Goals

The fact that health systems have struggled to integrate insurance financing into their care operations has left a legacy of at best partial integration. According to business historians, the core strategic idea at the root of these policy proposals was flawed; health insurance and care delivery are very different businesses, in some ways diametrically opposed to one another.

Hospital enterprises owning a health insurance business are thus engaged in unrelated diversification, a strategy that has long since lost favor in the business world due to poor returns on the investment. Robert Burns and colleagues found that the greater the investment in this type of diversification, the larger a health system’s losses. As we have argued elsewhere, Kaiser’s success looks increasingly like a one-off example. More than 80% of Kaiser’s enrollment remains in its originating Pacific Coast markets where it originated more than 70 years ago.

And despite more than a decade long federal push for “value-based” payment and tens of billions invested by health systems in consulting and infrastructure, by 2020, capitated payment accounted for a scant 1.7% of median hospital revenues and risk-based payment (e.g. two-sided ACO-style risk) only 1.1%. Neither revenue source has grown measurably since 2014 (Moody’s Investor Service, 9 Sept 21). Almost 50 years after the HMO Act of 1973, in only a few communities in the country (Pittsburgh, San Diego and Portland) do at least two integrated delivery systems compete for health plan enrollment.

Realistically, the Ellwood/Enthoven vision of a care system reorganized into risk bearing IDNs is not going to happen in the US. Yet the hospital and physician consolidation catalyzed by that vision has left most metropolitan areas with a few dominant health systems with undeniable market power in their commercial transactions with health insurer. This market dominance and observed pricing power has led to an increasing policy hostility towards health system scale, with commercial prices being used as the singular measure of performance.

Meanwhile, other large corporate actors have appeared that seek to integrate care across regions without owning hospitals. The two largest enterprises in the US health system, each exceeding $250 billion in annual revenues, do not own a single hospital. They are UnitedHealth Group and CVS/Aetna, diversified health insurers with impressive arrays of primary and ambulatory health services as well as pharmacy benefits management and operations and in CVS/Aetna’s case, a nationwide chain of retail pharmacies. How one pays or regulates these vast non-hospital enterprises, just two of which accounted for more than 13% of US health spending in 2020, in a way that maximizes societal benefit is a conversation that has not even begun.

How to Think about Measuring Social Benefit from Large Health Systems

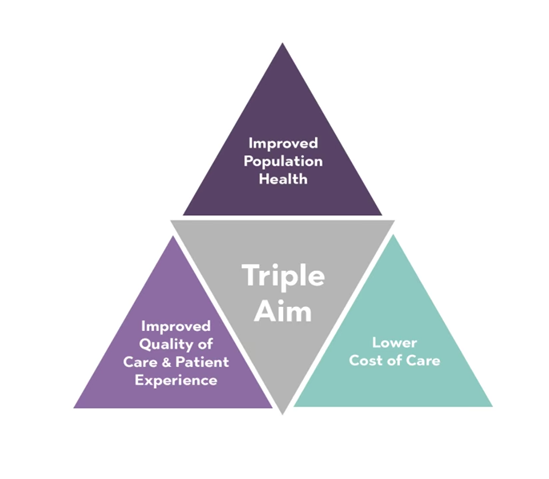

It is not clear to us that having a highly fragmented health system with thousands of actors each covering a piece of our health needs and competing aggressively on unit price is in the society’s best interests. A comprehensive conceptual framework for assessing the social contribution of complex health systems—hospital-centric or not—is needed. Fortunately, Donald Berwick did exactly such a thing in 2008 by proposing what he called the Triple Aim. While Berwick meant it to represent achievable goals for health systems, we think it is also valuable as a societal benefit framework measured across a region.

Berwick later added a fourth Aim, improving the work experience of clinicians, in recognition of the challenges of professional burnout and stress, which have been dramatically heightened by the COVID crisis.

In applying Berwick’s formulation, it is not whether a system exceeds a certain numeric threshold of market concentration, but how the merged entity affects its communities’ health and welfare after the attorneys and consultants go home that really matters.

More specifically, a health system’s societal contribution should be evaluated based upon:

- Its ability to reduce per capita care costs in the populations they serve

- Its ability to reduce errors and increase measured patient satisfaction by improving the care experience.

- Its ability to improve population health in their communities, especially by attacking and ameliorating social determinants of health.

- Its ability to engage clinicians and improve their practice efficiency and satisfaction.

Let’s discuss each of these and consider the ramifications for social benefit.

1. Per Capita Cost Reduction

Traditional anti-trust enforcement has focused on commercial price behavior as the measure of social impact of a merger. Yet modern systems offer thousands of products, each of which has a unique charge structure spread across multiple payers. Systems also differ markedly in the degree to which they serve government funded patients whose insurers (e.g. Medicare and Medicaid) pay less than the fully loaded cost of care, and thus rely on commercial insurance markups to offset these losses.

However, the communities they serve generate health costs summed across all the people who live in a given region. Berwick believed that reducing per capita medical expense for the community as a whole was the highest and best use of health systems, whether or not they were paid for all those patients on a capitated basis. Since it is not realistic to expect that we will convert all provider payments to capitation, health systems will have to manage the tension between per incident payment for services and overall population level reductions in health expense. The burden of proof will lie in evaluating the specific mechanisms systems use to reduce per capita expense.

These mechanisms could include the use of targeted comprehensive primary care aimed at older and chronically ill individuals, including the use of “extensivists”—primary care physicians and advanced practice nurses that reach out into the home and workplace to manage health risks proactively, the development of palliative care models for patients with advanced illness, employing digital/telehealth services that target not only chronic illness but also various forms of addiction, particularly to food, alcohol and opiates, telehealth tools that improve adherence to risk-reducing medications like statin drugs, vaccines and the use of predictive analytics, disease registries, and “hot spotting” of vulnerably co-morbid patients, among many other promising innovations.

North Carolina’s Novant Health has used community health workers who assess high utilizer patients for social determinants in their home, shelter, or location of choice. They connect patients to a variety of trusted community partners, addressing food, housing, workforce development and transportation barriers

The result: a 33% reduction in ED utilization, a 40% increase in medication adherence, and a 21% reduction in PHQ-9 score (measuring anxiety and depression). According to Novant Health CEO Carl Armato, the most consistent piece of feedback from CHW patients is gratitude that someone took time to listen to and address their needs–they consistently report a remarkable patient experience.

Simply focusing on commercial prices as a metric of performance of health systems misses any recognition of the market context these systems operate in such as neighborhood poverty, racial and economic inequity, payer mix and disease burden and thus fails to address the financial viability and sustainability of these enterprises. How many large health systems, particularly Academic Health Centers, would survive in the face of an arbitrary Medicare-related price ceiling for commercial payment?

We advocate a more nuanced assessment of economic contribution that balances an examination of per capita cost with the overall financial performance of health systems[1]. Since community wide per capita spending is difficult to capture, per capita Medicare spending would be a more easily accessible proxy measure.

2. Improving Safety and the Patient Experience

Health system consolidation should lead to systematic improvements in the patient experience. COVID clearly showed that larger health care organizations with significant IT systems and technical staffs were better able to scale up telehealth operations to compensate for the loss of in-person elective and emergency care and to sustain telehealth use when elective care resumed. The ability to stand up command centers and manage health resources (ICU beds, emergency rooms, clinical staffing and related support services) across a metropolitan area or region cannot be achieved by a large number of competing, freestanding facilities.

The ability to create condition-specific care plans that envelop and extend complex care episodes (e.g. joint replacement, cardiac nerve ablation, etc) is enhanced by having multi-disciplinary clinical teams supported by data analytics and IT systems. Similarly, the ability to identify defects in clinical and administrative processes that expose patients to risk and to wasted time and cost is enhanced by having a larger base of participating clinicians.

Pre-COVID, many health systems were building “digital front doors” to their care systems, using smartphone apps, call centers and digital health access to smooth entry into and passage through their care systems. Larger systems created by mergers have not only enhanced clout with regional clinicians but also with health insurers that should be used to bring down patient bills.

These improvements should be measurable through improved HCAHPS ratings and rising net promoter scores. Similarly, reduced clinical errors and improved clinical productivity are measurable and should be discoverable by patients and community members.

3. Improving Population Health through Addressing Social Determinants

In his “Poverty and the Myths of Health Reform,” the late Dr. Richard (Buz) Cooper persuaded us that the most important intervening variable in the widely observed variation in hospital and specialty use from community to community was not the supply of specialists and hospital beds, but rather the prevalence of poverty—the main social determinant of health. Homelessness, food insecurity, broken families, unemployment, health illiteracy all stem from poverty, and generate both avoidable illness and costs.

These conditions cannot be ameliorated by health systems, or “competition” between isolated pieces of the care system, because they ultimately originate in our culture and society. The United States has grossly underinvested in the social care needed to ameliorate these conditions. These underlying social conditions that drive a lot of “unnecessary” health care use cannot be ameliorated through the core businesses of health systems, but rather through their collaboration with other entities with community wide reach, as well as neighboring public health systems—the very kind of collaboration we saw across the country during COVID.

There are many examples of this type of collaboration:

- California’s public health collaborative to attack and reduce maternal mortality, in which hospitals played a decisive role. This multi-year collaboration succeeded in reducing maternal mortality by more than half to rates comparable to western Europe, with concomitant reductions in PICU stays, infection-driven lengthy hospital stays, etc.

- Blue Zone Collaboratives. These collaboratives focus on specific neighborhoods or districts, and identify gaps in access to food, housing, public safety and social/human services that, when ameliorated, contribute to lengthening life expectancy in the geography chose. Health systems are key actors in most of the 56 projects currently underway.

- Mental Health Collaborations. In many communities, both public and private mental hospitals have closed, and services for those in mental health crisis have been absorbed, with predictable results, by local law enforcement. In metropolitan Seattle, health systems that normally compete for patients—MultiCare and CHI Franciscan Healthcare—collaborated to build a $41 million 120 bed inpatient psychiatric facility

- Addressing Homelessness. Numerous health systems (including Kaiser Permanente, Promedica, Truman Health, etc. ) have moved to create living spaces for homeless people in their communities, which has vastly simplified bringing community-based services and job opportunities to them.

Many health systems are engaging community partners in addressing income inequality, unemployment, educational opportunity, food insecurity, homelessness and racism. Some health systems such as Promedica in Ohio and Novant Health in the Carolinas are making upstream investments in housing and social services and to act as “anchor institutions” for community development. Other systems such as Ohio Health and Inova Health focus on their core clinical mission but embrace partnerships with community organizations.

Novant Health has created a program for “Expanding Opportunity through Education”—investing in education programs with students of color and economically-disadvantaged communities where there are significant disparities in college readiness rates. Individuals who do not graduate high school are more likely to report suffering from at least one chronic health condition—asthma, diabetes, heart disease.

Under new CEO Dr. Stephen Jones, Virginia’s Inova Health System has a partnership model for community engagement. Inova established twenty care clinics in zip codes of need based on data and community input with over 100,000 visits in 2021. Realizing the effects of what Jones terms “social drivers of health” the Inova Cares Clinics house Community Health Workers embedded in the neighborhoods to build trusting relationships, as well as pantries to address food insecurities. In addition, in partnership with local Title I schools and non-profits, Inova is working to create career journeys for students. Inova also supports 30 community organizations through health equity grants totaling $1M to leverage relationships for real impact in the community.

The normative expectation should be that because larger health systems serve larger populations, and therefore are exposed to larger community risk factors and needs, they can and should be expected to devote resources and talent to addressing them. The existing approach to evaluation of community benefits (as in the IRS definitions and the requirements under the Affordable Care Act) are sorely in need of re-examination to account more fully the range of initiatives being pursued.

4. Improving Care Giver Experience

One area where large health systems have struggled is in improving the working lives and professional satisfaction of its caregiving workforce. COVID clearly demonstrated how much stress and pressure in health systems devolves onto front line care givers. While large health systems were ultimately able to procure the PPE needed to make their jobs safer, they were less effective in ameliorating the stress at the root of care during this crisis. Being highly dependent on an aging workforce, health systems face huge staffing gaps in the wake of COVID as burned-out baby-boom vintage doctors and nurses retire or transition to other, less stressful work roles.

Health system leaders are acutely aware that their clinical workforce are “spent” after more than two years of delivering front line care in a pandemic, increasingly to unvaccinated and often hostile or violent patients. It has become a strategic imperative that health systems respond effectively in acknowledging and managing the mental health problems of their clinical workforce. Failing to acknowledge this problem has resulted in avoidable shortages in clinical staffing, and excessive reliance on mandatory overtime and temporary clinical workers or travelling nurses.

Clinician engagement is an important precondition for improving clinical quality and reducing medical errors. Large health systems have fewer excuses for not having worker sensitive (as opposed to litigation sensitive) human resource policies. Workforce satisfaction is easily measured through physician and staff engagement surveys.

Conclusion

We do not propose this performance framework as a regulatory guide for state or federal authorities. Rather it is presented as a voluntary alternative for managements and Boards seeking to demonstrate the community benefits created by their institutions.

At their best, large health systems can deliver sophisticated, complex care to their communities. But they can also play a key role with community partners in addressing the social determinants of health, thus reducing per capita health cost. Large multi-billion health systems are here to stay. The conversation about how to enhance the health systems’ benefits to their communities, which have been so vital during COVID, has barely begun.

Jeff Goldsmith is President, Health Futures Inc & Ian Morrison is the former President of Institute for the Future. One of them is America’s best known health futures, but we’re not sure which!

Acknowledgements

This essay has benefitted greatly from review, comments and examples provided by colleagues. In particular, we would like to thank health system CEOs and health policy experts Nancy Agee, Carl Armato, Carmela Coyle, Stephen Jones MD, Chip Kahn, Stephen Markovich MD, Tom Priselac and Michael Gentry.

[1] Nancy Kane, Robert Berenson and colleagues have pointed out that the financial performance of health systems differs materially based on their resource position, payer mix and other variables, and proposed a financial performance evaluation framework based on audited financial reports to account for these differences . The same is true of the geographical areas served by systems; those which serve communities like the Bronx or South Central Los Angeles face greater challenges than those serving suburban communities. Adding socio-economic domains based on geography to the Kane/Berenson framework would facilitate “apples to apples” comparisons of potential social benefit created by systems.

Categories: Uncategorized