By CASEY QUINLAN, HELEN HASKELL, BILL ADAMS, JOHN JAMES, ROBERT R. SCULLY, and POPPY ARFORD

Last year, the Patient Council of the Right Care Alliance conducted a survey in which over 1,000 Americans answered questions about what worried them most about their healthcare. We asked questions about access to care, concerns about misdiagnosis, and risks of treatment, which we reported on in our last THCB piece about the What Worries You Most survey.

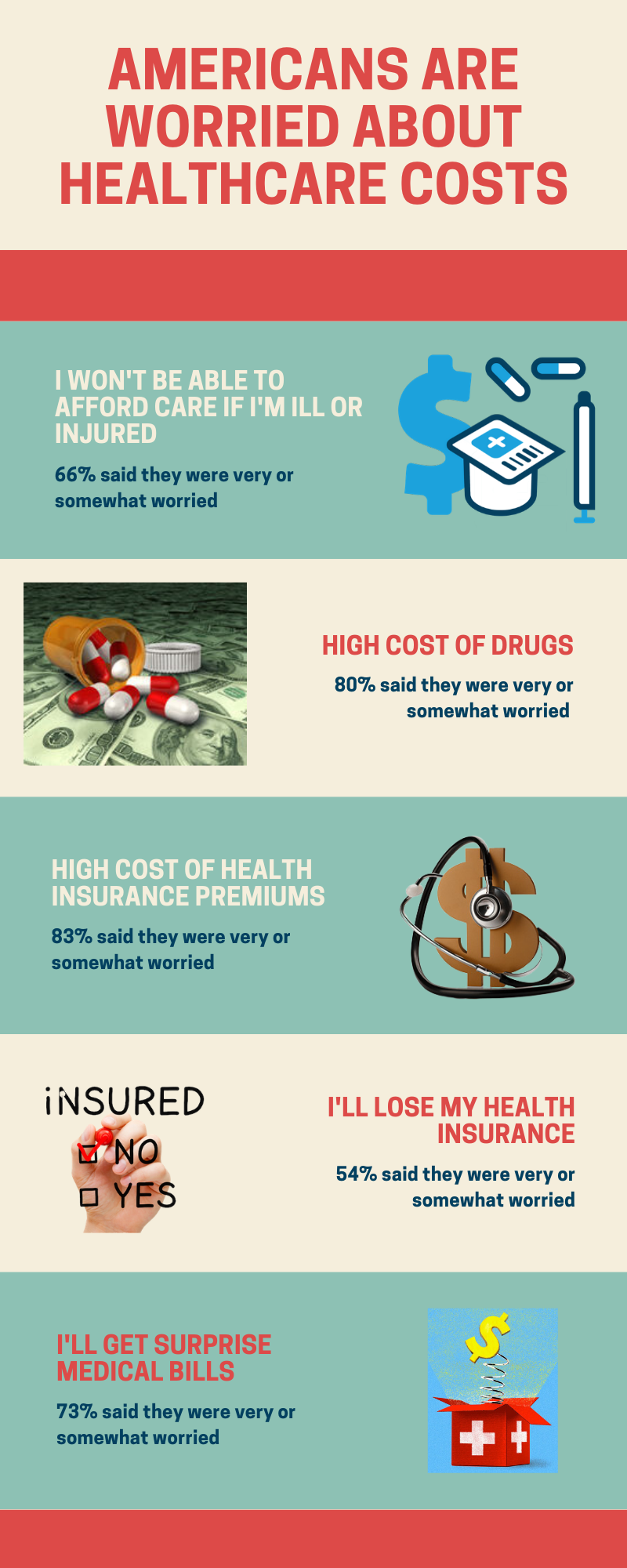

We also asked people to rank their concerns about the costs of their care, in five questions that covered cost of care, cost of prescription drugs, cost and availability of insurance, and surprise billing. In the time since we ran the survey, everything has changed in American healthcare. The COVID19 pandemic is filling emergency rooms wherever the epidemic arrives. Bills are likely to be high, for both patients and insurers, and it is still far from clear how they will be paid. Americans are likely to continue to worry deeply about healthcare costs, with good reason, since it’s only in America that someone can go bankrupt due to seeking medical care.

Below are the questions we asked, and some commentary on how survey sentiment might be impacted by the COVID19 pandemic:

1. I can’t afford my care if I become ill or injured. Sixty-six percent of our survey respondents said they were very or somewhat worried about affording care if they got sick, or were hurt. Even if you have “good insurance,” usually an employer sponsored plan through work, you may have a high deductible or a narrow network of providers, leading to those pesky surprise bills. If you have insurance through the Affordable Care Act insurance exchanges, your situation is likely to be worse: your networks may be extremely limited and your total out-of-pocket payments can be as much as $14,000 per year for a family plan. Now, COVID19 marches across the globe, with economies shuddering under the weight of business closures and layoffs due to social distancing requirements. We’re beginning to see the impact on employer sponsored insurance coverage, with people furloughed or laid off due to the pandemic. If furloughed, they might still have insurance; if laid off, they’ll have to apply for COBRA coverage, but only if their employer had 20 or more employees. And there were still 27 million Americans without health insurance before the COVID19 pandemic hit, so there’s a deep well of worry about how to pay for healthcare – COVID-related, or not – that continues to deepen. For one uninsured patient in Boston, the price tag for her COVID19 treatment, which didn’t include hospitalization, was almost $40,000.

2. High cost of drugs. Eighty percent of responses to our survey indicated they were very or somewhat worried about prescription drug prices. Insulin, a drug that has been available for over 100 years, and which is critical to the lives of those who take it, is now priced at up to $300 per vial. Now, in the COVID19 crisis, diabetics are worrying about availability as well. Recent headlines have trumpeted the promise against COVID19 first of antimalarial drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, and now of remdesivir, an antiviral drug developed in the fight against Ebola. Enthusiasm for hydroxychloroquine has waned following early studies showing potential harm and lack of effectiveness, but at the height of the craze retail prices for the anti-malarials ran between $100 and $350 per prescription. Concerns over quality also arose as the FDA pressed previously sanctioned manufacturers into service. Remdesivir, still an experimental drug, has yet to be priced by Gilead Pharmaceuticals, but drug pricing insiders are predicting a per-treatment cost of over $4,000.

3. High cost of health insurance premiums. Eighty-three percent of our survey respondents said they were very or somewhat worried about health insurance premium costs; averaging over $15,000 per year for a family with employer sponsored insurance (employee’s portion averages $5,000) the U.S. regularly wins the prize for “most expensive national health coverage.” During the COVID19 pandemic, early signals indicate that U.S. health insurers are benefiting from the downturn in elective healthcare, with Anthem beating 2020 Q1 profit estimates, Humana also beating estimates, and UnitedHealth, the biggest American health insurer, beating Q1 profit estimates, too.

4. I will lose my health insurance. Fifty-four percent of survey respondents said they were very or somewhat worried about losing their health insurance. Given that 49% of Americans are covered by their employers, the huge shift in unemployment numbers as COVID19 hit the American economy – almost 15% unemployed as of the end of April, 2020 – means that many of those who were worried have likely had their worries validated by now, and those who weren’t worried might have shifted to “very worried.” The Healthcare.gov marketplace has instituted a Special Enrollment Period for people who have lost their jobs, and their employer sponsored coverage, due to COVID19. However, if your employer didn’t offer health coverage, and you didn’t have ACA coverage on your own, you won’t qualify for that Special Enrollment Period.

5. I will get surprise, unexpected medical bills. Seventy-three percent of those who responded to the survey were very, or somewhat, worried about surprise medical bills. The responses to question #1 (affordability) are echoed in the responses to this question, since even with insurance, an emergency health crisis may become a financial crisis if the care you get is out of network for your insurance coverage. With private equity taking a bigger position in healthcare via buying up doctor groups and medical practices, the risk of surprise billing has grown rapidly in recent years, and made national headlines in 2019, when Congress started gearing up to work on legislation to end it. Lobbying efforts from the industry side, including an ad blitz, stopped it cold. This may be changing with COVID. To the surprise of many, HHS conditions for the provider relief payments authorized by Congress declared, “HHS broadly views every patient as a possible case of COVID-19” and stipulated that “for all care for a possible or actual case of COVID-19,” the provider could not charge rates higher than those of the patient’s own insurance company. While it is still unclear, this is interpreted by some as a ban on all surprise billing for the duration of the epidemic. The federal laws are only one part of a patchwork of measures being rushed into place to help provide treatment for both insured and uninsured coronavirus patients. But as the maze of relief measures meets the maze of U.S. healthcare coverage, many loopholes and questions about coronavirus billing remain. The big question remains what permanent changes this crisis might incite, in a system that has previously left too many people out in the cold.

“Wallet biopsy” has been a feature of U.S. healthcare for a long time, with a patient’s financial and insurance status being the key to getting anything from trauma care to an organ transplant. In that climate, consumer worries about their personal financial risk when they seek medical care are totally rational. There are no price lists on the walls of hospital emergency departments, or even in family practice medical offices. Given that the current COVID19 pandemic is forcing many people into hospital ERs, the ultimate price tag for care – for individuals, and as a nation – is still being tallied. Worrying about the costs of care is baked into the American consumer’s psyche at this point. The challenge for us, as a nation, is to use this as a pivot point to create a more rational, less arbitrary, system of payment for healthcare, one that does not allow corporate lobby power to thumb the scale on building that rational, national system.

The authors are the Leadership Team of the Lown Institute’s Right Care Alliance Patient Council: John James, Patient Safety America, Robert R. Scully; Casey Quinlan @MightyCasey, Bill Adams @Poorcountryboy2, Helen Haskell @hhask, and Poppy Arford.

Categories: Uncategorized

” There are no price lists on the walls of hospital emergency departments, or even in family practice medical offices.”

As in the Rolls Royce show room, if you have to ask the price, you can’t afford it.

“one that does not allow corporate lobby power to thumb the scale on building that rational, national system.”

You’d have to change the political reward system of legislators. Corporations and their lobbyists pay for campaigns, perks, jobs after politics, and jobs for their families and friends. No politician comes out of politics with less money than they went in with.