By ANISH KOKA

Frances Oldham Kelsey by all accounts was not mean to have a consequential life. She was born in Canada in 1914, at a time women were meant to be seen and not heard. Nonetheless, an affinity for science eventually lead to a masters in pharmacology from the prestigious McGill University. Her first real break came after she was accepted for PhD level work in the pharmacology lab of a professor at the University of Chicago. An esteemed professor was starting a pharmacology lab and needed assistants, and the man from Canada seemed to have a perfect resume to fit. That’s right, I said man. Frances was thought to be a man’s name, and the acceptance letter accepted Mr. Frances Oldham. Given the times, her Canadian mentor advised the young Frances she not write to inform the Chicago professor of the mistake but to simply sign the acceptance letter as Miss Oldham. The rest, as they say, is history. Ms. Frances Oldham arrived in Chicago in 1936, and just two years later was asked to work on figuring out what caused one of the worst poisonings in American history by the nascent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The FDA at the time was a small organization within the federal government that had come into being a few decades earlier after the passage of one of many progressive laws passed to protect consumers from rapacious pharmaceutical companies of the day. At the time there was no standard for claims that could be made to an unsuspecting public and no requirement that drug companies specify what ingredients were being consumed by the public. The companies of the day would take alcohol, water and coloring mixed together – give the formulation a name, get a US patent, and make millions by heavily marketing testimonials of cures to all that ails directly to the consumer. At one point, it was estimated that there was more alcohol being sold via ‘patent medicines’ than at liquor stores.

Sadly, it was not medical professionals that put a stop to this, but muckraking journalists like Samuel Hopkins Adams who exposed the seamy underside in a series of articles for Collier’s Weekly entitled The Great American Fraud. Popular outrage followed publication of this series in 1905 and in response, the first draft of the FDA came into being by order of Congress in 1906.

The initial purpose of the FDA was a small, but important one – ensure the correct labeling of drugs being sold to the public. The 1906 act – fought tooth and nail by industry – mandated that ingredients such as alcohol, cocaine, heroin, morphine and cannabis be accurately labeled with contents and dosage. To understand the scope of the problem at the turn of the century, understand that Coca-Cola (Coke) was sold initially as a ‘patent medicine’ that was marketed as a cure for headaches, impotence, morphine addiction as well as a number of other ills. The main ingredients? Cocaine and Caffeine. Current drinkers of Coke will be happy to know that cocaine was eliminated from the formula in 1903.

The FDA as we know it now is a result of the passage of the Federal, Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) of 1938 that came as a reaction to national tragedy in 1937 that once again drove home the point that the public needed protection from private corporations. The matter was a simple one that involved an ingredient that actually worked – sulfanilamide. Sulfanilamide was an antibiotic that killed bacteria by preventing the synthesis of Folic Acid. Humans are relatively primitive and don’t make Folic acid – so it isn’t toxic to humans. That is, unless you’re the chief chemist of S. E. Massengill Company, and you create a preparation of sulfinilamide that is dissolved in di-ethylene glycol (DEG). DEG is toxic to humans – the first case reports of toxicity had been reported six years earlier. Unfortunately the chemist, Harold Watkins, who worked for the company was unaware as this was not widely known at the time. Watkins simply added some raspberry flavor to the sulfa dissolved in DEG, and the company founded by a Tennessee medical student who saw more opportunity in selling drugs to doctors than practicing medicine started distributing the drug widely. No animal studies or any type of premarket testing was required at the time, and so the drug went straight from the lab to the consumer. More than a hundred people died.

Figuring out what was happening fell to the FDA, and it was investigative work by Kelsey working in her Chicago lab that ultimately lead to the identification of DEG as the culprit. Months later, the FFDCA act passed, effectively changing the scope of the FDA from ensuring proper labeling, to safeguarding the public from known and unknown formulations of drugs.

The nation found itself engulphed in World War 2 shortly after, and all the resources of the nation were diverted to the war effort. Pharmacists like Kelsey worked to solve the problem of the day – create a synthetic anti-malarial for troops fighting in mosquito infested lands. There was no synthetic anti-malarial that came of the effort, but in working with a pregnant rabbit model Kelsey learned drugs could affect mothers very differently from their fetuses.

The experience with sulfilinimide and the work with antimalarials would soon be brought to bear after Kelsey was hired in 1960 by the FDA to help oversee the approval of new drugs. A few months after starting, an application from the William S Merrel company in Cincinnati lay on Kelsey’s desk. There was a new German drug – thalidomide – that the Merrell company sought to sell in the United States. The drug was meant as a mild sedative for pregnant women with morning sickness. It was already approved in multiple other countries and being prescribed by doctors widely. This was a chip shot. A stamp was all that was needed. But, the three-person team was not happy with the animal studies presented or the clinical studies which essentially amounted to testimonials from doctors. While Kelsey delayed the application asking for more data, the company grew more and more irate, pressing approval of the drug for what they felt was going to be a profitable Christmas season. The bureaucrats won the day. Slowly a trickle , and then like a flood came stories from pediatricians of babies born deformed with tiny limbs. The final toll was gruesome – 10,000 affected in 46 countries. There were only 17 reported cases in the United States. And so it came to pass that a bureaucratic delay saved thousands of lives.

The story was reportedly leaked to the Washington Post by politicians attempting to pass legislation to further expand the FDA’s scope and ran under the headline “Heroine of the FDA keeps bad drug off market”. Shortly after, the Kefauver-Harris drug amendment was signed into law by John F Kennedy, creating the FDA we would recognize now. Drug companies had to prove efficacy in addition to safety, and it was going to take a lot more than physician/patient testimonials to prove it. The law also put the FDA in charge of advertising, as well as manufacturing quality.

It is a beautiful story. But there are other stories.

Diane

Diane came to the emergency room with unbearable chest pain. She was 52, had struggled with controlling her blood pressure, but was otherwise well, until she suddenly wasn’t. It was like there was something ripping and tearing in her chest. The main pipe that serves as the conduit from heart to the rest of the body is called the aorta. The walls of the aorta are made of multiple layers to withstand the pressure wave generated by each heartbeat. Making it to 70 years of age means the aorta will withstand over 30 million pulsations. It is a remarkable thing that we don’t all die from exploding aortas once we hit the 10 million mark. Some aren’t as lucky as others – the higher the stress on the aorta the greater the chance a microscopic tear forms in the innermost layer with one of those pulsations. The whole wonderful system begins to fail with that small tear. Each pulsation now makes the tear bigger. Eventually blood forces it’s way into the tear, and the innermost layer starts to be torn away. It’s like your insides are being ripped apart. This was Diane’s problem. Mortality for the patients lucky enough to make it to the hospital is measured in hours- the oft-quoted number is 2%/hour. The technical term is an ascending aortic dissection. There is little in medicine that is more acute. Something needs to be done to stabilize the aorta and usually this means rapid transport to an operating room where a cardiothoracic surgeon can saw through the sternum, arrest the heart, and replace the defective portion of the aorta. That patients like this survive is one of the miracles of modern medicine.

Diane was in the operating room an hour after coming to the Emergency Department. Minutes from starting, a problem emerged. Diane was on a blood thinner to treat a specific arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation. The anticoagulant was called apixaban, and it is commonly used by cardiologists to prevent the strokes normally associated with atrial fibrillation. There are three major classes of anticoagulants in wide use – Factor Xa inhibitors, a direct thrombin inhibitor, and Coumadin. The problem here is that the direct thrombin inhibitor, and Coumadin have an antidote, the factor Xa inhibitors do not. Apixaban is a Factor Xa inhibitor. There is no FDA approved antidote, no effective reversal agent. All one can do is wait for the drug to be metabolized. The instructions are to wait 24 hours for minor surgery, 48 hours for major surgery. Diane didn’t have 48 hours, and only had a flip of a coins chance of making it 24 hours. But cutting through the aorta when any cut made has little hope of clotting is a daunting proposition in its own right.

The team elected to wait. Diane was moved to intensive care. Analgesics brought some relief from the chest pain. Medicines were started to help reduce the shear stress from every heartbeat on the aorta to buy time. The next day came and went. 36 hours later she began to have more chest pain. Suddenly and abnormal heart rhythm developed. Minutes later she became unresponsive and lost her pulse. Half an hour later Diane was pronounced dead.

The proximate cause of death was paralysis on the part of the surgical team worried about uncontrollable bleeding. The surgical team pointed to the class of blood thinners Diane was on. Factor Xa inhibitors are a class of medications started somewhat gleefully every day by cardiologists. The underlying reason is typically an arrhythmia of the heart called atrial fibrillation that predisposes patients afflicted to strokes. It is believed small blood clots form in the heart of patients with atrial fibrillation, and are ultimately pumped into the brain, where occlusion of a vessel results in a stroke. The treatment shown to reduce the risk of this for years now has been the blood thinner known as coumadin – an inhibitor of Vitamin K dependent factors the body needs to clot blood. Coumadin is also known as rat poison – take too much, make the blood too thin, and death from internal hemorrhage results. Coumadin is a bear for patients and their physicians to deal with. Blood tests are sometimes needed weekly, and eating a varying amount of vitamin K in your diet causes dangerous fluctuations in blood thinning. The only upside of bleeding while on coumadin is that the rapid reversal of this effect is provided by transfusion of factors.

The difficulties of coumadin meant there was a market for alternative anticoagulants that were hopefully safer and easier to use. After decades of failure, three such agents hit the market just within the last 10 years. Pradaxa (dabigatran) inhibited the procoagulant thrombin, while Eliquis (Apixaban), and Xarelto (Rivaroxaban) bound and inhibited the procoagulant Factor X (ten). In each of the three randomized controlled trials patients given assigned to the new class of medications did just as well (Xarelto) or better (Pradaxa,Apixaban) than Coumadin at preventing clots being thrown from the heart. Remarkably, they did this despite being on a fixed dose of medication that didn’t require weekly/monthly blood tests to check the level of blood thinning. They also importantly reduced the feared complication of bleeds into the brain by half relative to Coumadin. The small problem, though, was that none of the new agents had an effective antidote. The drugs were approved knowing patients would bleed on them or need emergent surgery for some other reason with no effective way of reversing the effects of the drug. You couldn’t just give plasma or Factor concentrates as you did with Coumadin because the administered thrombin / Factor X would be inactivated by the circulating drug. The only thing to do was stop the drug and wait the 48 hours it typically took for the drug to lose effectiveness.

This did not stop cardiologists just like me from prescribing the drugs. After all, the drugs are equally as effective and reduced the rate of bleeding into the brain. Bleeds into the brain are very bad, and that even a reversal agent was no assurance of a good outcome. The best thing is to prevent a bleed, not deal with it after the fact. It also seemed highly likely that a reversal agent was around the corner.

Dancing with the FDA

Even with accelerated approval, the current FDA process takes years, not months. The first antidote developed was for the first class of novel anticoagulant that had hit the market, the direct thrombin inhibitor Pradaxa. Idarucizumab was a humanized monoclonal antibody fragment that bound Pradaxa and it’s active metabolites. The FDA approved the drug based on pharmacokinetic studies in healthy volunteers as well as a case series of patients on Pradaxa with life-threatening bleeding. Idarucizumab completely reversed the effect of Pradaxa on clotting times and was not associated with any major adverse events. The next antidote waiting in the wings for the only other class of anticoagulants – the Factor Xa inhibitors – appeared in the published literature months later. The new drug was called Andexanet and was ingeniously designed as a mimic to the body’s own Factor Xa, with some important mutations at critical sites that would prevent triggering of the normal coagulation cascade. Circulating Factor Xa inhibitors would bind the Factor Xa copy instead of the real thing and thus abolish the anticoagulant effect.

The first in man trials of Andexanet took place with healthy volunteers who were given either Apixaban or Rivaroxaban. After steady state of drugs was achieved, volunteers were infused andexanet or placebo, and anti-Factor Xa levels were measured serially for 12 hours.

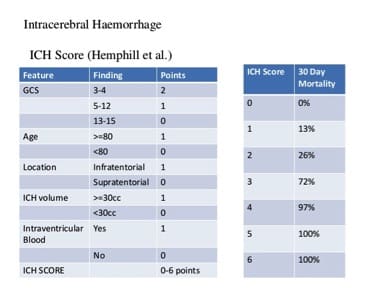

The results were remarkable – anti-Factor Xa levels fell immediately after infusion of Andexanet. A two hour infusion of antidote to follow the initial bolus kept anti-Factor Xa level suppressed for the duration of the infusion. No serious or severe adverse events or thrombosis was noted. Anti-Factor Xa is of course a surrogate marker for bleeding. Though there are strong links between bleeding control and anti-Factor Xa activity in animal studies, and the correction of Factor levels in Hemophiliacs is a well accepted marker for abolishing coagulopathies, patients and their doctors care about bleeding stopping, not what the anti-Factor Xa level is. Outcome studies in this space are challenging in part because not every patient may necessarily benefit from andexanet. Bleeding may stop spontaneously in many cases for many reasons with the conventional approach of just waiting. After all, the placebo graph shows Anti Factor Xa levels fall 50% in 12 hours doing nothing. When bleeding into the closed compartment of the brain, the hope is that the amount of brain tissue necrosis that results from the consequent disastrous rise in pressure in the cranium may be ameliorated by decreasing the amount of bleeding. Unfortunately, we don’t have a great way of quantifying brain cell death. The Intracranial Hemmorhage (ICH) score is a commonly used system to help predict mortality in patients presenting with bleeding in the brain. It is a six point scale that incorporates volume of bleeding, age, neurologic dysfunction at presentation, and location of bleeding to predict mortality.

Other than pointing out the information lost when a continuous variable is made categorical, what stands out is the nonlinearity of outcomes relative to ICH score. An ICH score of 3 is not a little worse than a score of 2, it is a lot worse. Mortality jumps from 26 to 72%. Harm increases in a non linear fashion. While the volume of blood gets only one measly point, it is the central problem – an obtunded patient with 5 ml of blood is probably not in that state because of the blood. The problem in relating just the volume of blood to outcome is that everyone’s intracranial compartment is different. 80 year olds have more space to accomodate a certain volume of blood than a 40 year old because the brain atrophies with age. Certain parts of the brain are more critical than others – a small volume of blood in the brain stem may be worse than a larger volume of blood in the frontal lobe. So a combination of volume of blood, location of blood, and the clinical effect of bleeding determine prognosis.

With these difficulties in mind, the next adenxanet study tested the antidote in 67 patients with severe life-threatening bleeding within 18 hours of administration of a Factor Xa inhibitor. The coprimary endpoints were anti-factor Xa activity and the rate of good or excellent ‘hemostatic efficacy’. With regards to head bleeds, a reduction in volume of blood relative to baseline <20% was termed excellent, <35% was termed good. Of the 47 patients in the efficacy population, 37 patients were adjudicated as having good or excellent hemostasis. Anti-Xa activity levels decreased significantly after bolus and infusion of andexanet as well.

With regards to safety the concern with any antidote to a drug that causes bleeding is too much clotting. Recall that Adenxanet is engineered without critical sites that normally catalyze thrombosis, and that in healthy volunteers, no thrombotic events were reported. The population of patients presenting to ERs with life-threatening bleeding however, are a whole separate ball of wax. The published article helpfully lists everyone who had either a death or complication.

This group of elderly patients arriving at the hospital with any acute illness, let alone life threatening bleeding have a significant background rate of morbidity and mortality with standard of care. It is, of course, hard to say with certainty without an appropriately matched control group whether the rate of thrombosis is higher after andexanet. The study was also not designed to assess actual outcome differences. We don’t know if patients are any less disabled because we were able to reduce their level of anti-Factor Xa activity.

But the data seemed more than good enough, and Portola Pharmeceuticals, bay area biotech firm that makes Andexanet first submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) in 2015. The FDA responded in Auguest of 2016 with a surprise rejection in the form of a Complete Response Letter (CRL). These communications are private, but the company at the time noted that the FDA was primarily concerned about the quality of manufacturing facilities for the drug. One year after the rejection, Portola reapplied in August 2017 expecting to hear from the FDA in February 2018. February came and went as regulators pushed their expected response to May 4th, and the CEO of Portola hinted at even further delays on an earnings call. Casually mentioned on the same earnings call was a net loss for 2017 of $286million , just slightly more than the $269million loss posted in 2016. Hemorrhaging money, stock price declining, much hung on the May 4th decision by the FDA.

The drug was approved.

Little details are public about what the company did to gain approval. The FDA did make approval conditional on performance of post-marketing RCT of usual care vs Andexanet. The drug will be available in limited fashion to 40-50 hospitals in late June of this year, with wider distribution and availability expected later in the year.

Unfortunately, all of this was too late for Diane. The eventual review of the case in a conference of cardiologists amounted to a giant shrug of collective shoulders. A small case series of patients who were operated on anticoagulation was presented suggesting high mortality of bleeding, and the collective conclusion appeared to be that there were mortalities that just couldn’t be helped. No one expressed any frustration that 3 years had passed after publication of the positive trials, and still, no antidote was clinically available.

We have come a very long way from cocaine laced Coke being sold to patients to cure morphine addiction. One wonders if we have traveled too far. An approval process for an antidote to life threatening bleeding now takes hundreds of millions of dollars and years of regulatory approval. There are clearly patients dying as a result. Is anyone counting?

Even with approval, a post marketing RCT will require clinicians to choose patients with life threatening bleeding to not administer andexanet to. Will it be a patient like Diane? I imagine the argument for another trial, and slow approval relates to concerns a Perhaps some will raise the uncertain safety profile because of the lack of a comparison group in the only trial in a real world setting. That would be unfortunate because this is a poor way to navigate the real world. Any clinician taking care of Diane would have taken their chances with what is known about Andexanet now. There is an intuitive understanding about the potential upsides and downsides that doesn’t require a strong mathematical foundation in game theory, and certainly does not require knowing anything about p-values.

Nassim Taleb, the mathematician/philosopher/flaneur conceptualizes what should be clear to physicians uninfected by the average treatment effect virus as decision making under non-linear conditions.

There are large outsize gains here to operating to repair the aorta in a timely fashion with the blood thinner neutralized that vastly outweigh risks. The best thing about the graph is that it incorporates uncertainty – it does not require one to know exactly which direction from the starting point any given patient may travel. Because traveling to the right results in outsize gains, one doesn’t have to ‘win’ much to come out ahead. To be clear, it helps, of course that the gain here is the chance of life with surgery vs. certain death without surgery, and that the probability of pain/harm as suggested by biology and demonstrated in the trials to date suggest harm related to Andexanet is low.

In the parlance of Taleb –

Regulators should worry more about efficacy than harms in the face of convexity.

(The threshold for approval of an antidote for life threatening bleeding should have a low threshold for rapid approval if the drug has a high probability of being effective and a low probability of harm)

Physicians who have never heard of Taleb do this intuitively. Every day in some emergency room a trauma surgeon is working to find and stop the bleeding in a patient shot in the chest. Many of these patients will not survive – does this mean surgeons should cease their efforts to find and stop bleeding as soon as possible? Is there no point to innovating quicker ways to stop bleeding in service men and women in the field because most folks stepping on IEDs won’t make it?

None of this takes into account the significant costs that must be recouped for this type of an approval process. Portola plans to sell the drug for $27,000 per dose. It is estimated there are 100,000 admissions and 2000 deaths for bleeding related complications in patients taking Factor Xa inhibitors. The figure makes me groan because I know the drug will be reached for over and over again in EDs across the country, and it is entirely possible that a large proportion will not derive a significant benefit. The idea is significantly more palatable if the drug cost $2000. But given that Portola lost $500million dollars in the last 2 years alone, can we grouse for lower prices given the regulatory hurdles erected?

If we really are interested in helping patients , we will need to pay heed to impulses on all sides – that of profit seeking corporations to cut corners, and that of regulatory excess to overwhelm, stifle innovation, and raise cost.

Anish Koka is a Cardiologist in practice in Philadelphia. Troll him on twitter @anish_koka

Categories: Uncategorized

It shouldn’t take several years to approve a new competitor to manufacture a GENERIC drug that skyrocketed in price due to an insufficient number of competitors. Fortunately, the current FDA commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, made significant progress in addressing that problem. More staff can speed things up without compromising appropriate due diligence in evaluating both efficacy and safety.

Barry,

“The FDA as we know it now is a result of the passage of the Federal, Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) of 1938 that came as a reaction to national tragedy in 1937 that once again drove home the point that the public needed protection from private corporations.”

As in banking/financial regulation, reduced oversight leads to corruption and fraud, and in the case of FDA, even death. After all the smoke has cleared NO ONE GOES TO JAIL!!!! Just pay a fine and business as usual.

I don’t agree with your soft assessment of corporate intentions.

Peter, I don’t think drug companies are jerking R&D spending around to meet quarterly financial targets. Plenty of drugs fail before reaching Phase 3 trials. To win FDA approval, the new drug has to outperform a placebo to a statistically significant degree and have a reasonable safety profile including safe manufacturing processes. Where the new drug is priced and the extent to which it may be superior to existing treatments available at lower cost are completely separate issues.

As for regulation itself, not just in drugs but in lots of other areas as well, there is lots of room for improvement in streamlining review processes. At the FDA, the approval process could presumably be sped up by hiring more staff. A reasonable balance needs to be struck.

I support the FDA and feel safer with it doing public due diligence as private companies feel pressure to try to cut corners to make next quarter financials. When ever regulations are cut bad things happen.

Company has one other drug. Another factor Xa. But doesn’t matter.. company prices drug to make an overall pRofit. Doesn’t do them much good to price drug just related to Andexanets cost. Price of drugs has failure of other drugs built into it – just like price of Hospital stays has price of uninsured built into it.

Company reports being surprised by fda ruling. Letter not public , but seemed to relate to validation that they expected would be ok to do post approval , not pre.

They still reduce rates

Of ICH by half. Still a net +ve to approve them – even without antidote.

1) Andexxa is not the company’s only drug. Not sure how much of that loss is due to Andexxa and how much to its other drug.

2) It sounds like most of the delay in approval was due to manufacturing conditions. If those were valid, in some cases manufacturing has been halted due to mold growth or fine glass found in medication vials, then doesn’t your graph change the risk of harm, especially fixable, preventable harm, and increase it? (Also seems to me that there is always a bit of post hoc reasoning here. We know after the studies that it had a low risk of harm, not before. What about the drugs submitting studies that did have higher rates of harm?)

3) At the time these were approved, I had qualms about them without available reversal agents. It is not just brain bleeds.What would otherwise be run of the mill GI bleeds become exciting. trauma was a lot less fun when someone was on one of those drugs. That said, it looks like the follow on mortality studies, which should catch all bleeding, still showed lower mortality (except for dabigatran in some studies IIRC).

Steve

As so often in government regulation, striking a reasonable balance between risk and reward is easier said than done. It sounds like the “Frances Kelsey Syndrome” meaning to avoid signing off on what might turn out to be the next Thalidomide is to be avoided at all costs is still deeply ingrained in the FDA’s culture. Thanks for a fascinating and informative essay.