By ANISH KOKA

A recent email that arrived in my in-box a few weeks ago from an academic hailed the latest “paradigm shift” in cardiology as it relates to the management of stable angina. (Stable angina refers to chronic,non-accelerating chest pain with a moderate level of exertion). The points made in the email were as follows (the order of the points made are preserved):

- The financial burden of stress testing was significant (11 billion dollars per annum in the USA!)

- For stable CAD, medical treatment is critical. We now have better medical treatments than all prior trials including ischemia. these include PCKS9 Inhibitor, SGLT2-i, GLP1 agonists Vascepa and others

- CTA coronaries is by far the most important single test for evaluation of these patients

- ” the paradigm of ischemia testing may have come to an end”

- For stable angina (not ACS!) in most cases, the decision on revascularization should be based only on symptoms alleviation (as no survival benefit).

The general public should find it interesting, and not a random coincidence that the first point immediately gets to the financial burden of stress testing in a communication that is supposed to assess the level of evidence for the management of coronary artery disease. Imagine a cardiologist enters your exam room to talk about the chest pain you get every time you run up a flight of steps, and starts off the conversation with how much the societal cost of stress tests are. The cost of care is certainly a relevant concern, especially if it’s to be borne directly by the patient, but it would seem that the decision of whether a therapy is effective or not should be divorced from how much some bean counter decides to price the therapy to generate a certain return on investment. As such, the discussion that follows will omit any consideration of cost when evaluating the new ‘paradigm shift’ in management of coronary disease that is apparently upon us.

This particular debate boils down to the relevance of diagnostic testing for coronary artery disease. The traditional approach to testing is a functional test that utilizes the uptake of radioactive isotope injected into a patient during stress and rest conditions to identify mismatches in blood flow in the two states to identify myocardial ischemia. The amount of ischemia can be quantified as percent of total myocardium, and has been well correlated with prognosis. Having lots of ischemia typically means a much shorter lifeline than having little or no ischemia. The accepted paradigm in Cardiology has been to use traditional stress testing to triage patients to ‘conservative’ medical therapy or an invasive approach to bypass or open arteries via stents or coronary bypass surgery.

Of course part of the problem with technological progress in medicine is that in the zeal to play with fancy new toys doctors may not pause to ask whether they should be playing with the shiniest new toy. To be fair, progress in any field consists of traveling down paths not known to be deadends, and medicine is certainly not impervious to this particular law of nature. Nonetheless, the over-adoption of some new therapy or technology in American healthcare is supercharged by a third-party payment model that means the eventual self-correction is usually delayed, and the cost of persisting in dead-end pursuits is passed onto future generations of Americans in the form of ever ballooning debt. The story of opening arteries in the heart travels this same sad trajectory.

Humble beginnings on a kitchen table by a pioneer thought by many to be pursuing an insane path involved putting wires and balloons to dilate coronary arteries of a small select few patients with debilitating angina who didn’t want or weren’t candidates for the accepted therapy of the time: a cracked chest and a coronary bypass. The initial success of these efforts became a gigantic industry that needed to be fed by a consistent supply of patients. Now it was no longer the terribly symptomatic patient, but the minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic patient that found themselves in the hands of skillful operators that quickly opened arteries on a Monday, and had you back at work on Tuesday. Finding coronary disease became a very big business. That chest pain after eating a spicy enchilada could be a bad case of heartburn, but if you saw the right cardiologist, a trip to the stress lab could turn into a trip to the cardiac catheterization lab and a “life-saving” stent. This all happened despite the fact that it was well known from autopsy studies that many patients died with their coronary disease rather than of their coronary disease.

I want to believe the vast majority of cardiologists found themselves in a cath lab with a patient that had anatomically severe disease and felt compelled to address what they found in the hopes that the symptoms that initiated the cascade that brought them to this moment would abate when the artery was opened, and depending on how much cardiac muscle was distal to the stenosis being addressed, thought there was a good shot they were preventing a future morbid cardiac event. Regardless, the sheer volume of patients that were ending up in cath labs by the turn of the century should have been fair warning for the comeuppance that was nigh. Taking patients to the Cath Lab had been built on trials like ACME, where grizzled, stoic US war veterans were shown to have massive improvements in their symptoms by opening clogged arteries mechanically vs. the medical therapy of the time. Decades of indication creep later found a very different set of patients in Cath labs.

In 2007, a cardiologist fed up with the number of patients being intervened upon in cath labs finally did a study to prove what many suspected – opening up arteries in the contemporary average patient wasn’t saving lives. The study was hailed as revolutionary despite the fact that there had never ever been a study to suggest that opening up arteries in this group of patients would save lives. But regardless of the academic discussion of whether this was truly a ‘reversal’ of what cardiologists knew or not, the study that was aptly titled ‘COURAGE’ heralded an end to the profligate opening of arteries that had marked the prior many decades of cardiology practice. The number of stents that were placed for stable angina dropped markedly mostly because fewer and fewer patients with this diagnosis found their way to cath labs.

But there were some caveats to the COURAGE trial. A third of patients randomized to the medical therapy only arm, eventually crossed over to require a stent to open an artery. Waiting to open the artery for that third of patients was not associated with more heart attacks or death in the medical therapy arm overall, so it still seemed valid to take an approach to patients with stable angina that initially uses medical therapy, as this meant almost 2/3rd of patients never ever needed an artery opened.

The other knock on the COURAGE trial was that it didn’t apply to patients with severely abnormal stress tests. The trial actually excluded patients who were higher risk, and wasn’t a real-world trial because every patient ultimately enrolled had a coronary angiogram to rule out the really bad stuff before allowing randomization to the two arms. In the real world, a patient with some chest pain syndrome ends up with a stress test, and it’s up to the cardiologist to sort whether or not an abnormal stress test is indicative of meaningful disease that requires further action or not. Excluding the patients most likely to enjoy a survival advantage may be the ethical thing to do, but it does stack the odds against showing any mortality benefit to stress tests in a trial.

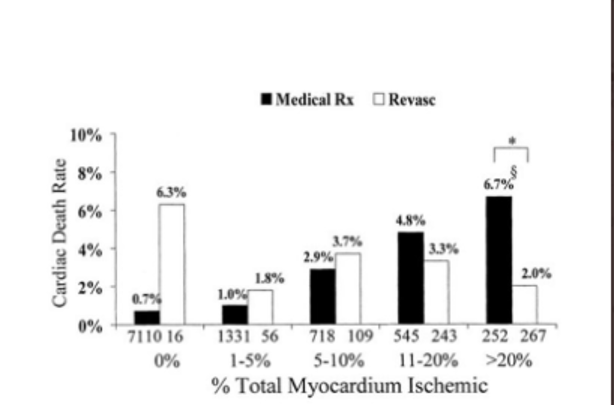

As the following figure from an observational dataset makes clear, it was only those with over 20% of ischemic myocardium that enjoyed a significant difference in cardiac death between medical therapy and revascularization of some sort. The figure also suggests that revascularization in lower risk groups is associated with numerically higher mortality in those who were revascularized. This data is from a prior era, and thus may reflect a time in which medical therapy was much less effective, but revascularization therapies were also more dangerous.

Still, it’s an important point: there was simply no basis to suggest revascularizing patients with small or even moderate amounts of ischemia would result in prolonging life. If the COURAGE trial had been positive, it would have been a shock.

As a result, even after COURAGE most cardiologists continued to believe it reasonable to offer revascularization to those with large amounts of ischemic myocardium. This isn’t just based on the inherently biased observational dataset, it’s because every cardiologist has seen high risk patients decompensating during a stress test. The functional tests in these patients are the most impressive – the ashen color as a drop in blood pressure with exercise as you watch the ventricle go from Normal to markedly abnormal. These patients are rapidly sent for what is currently believed to be life-saving invasive revascularization.

COURAGE didn’t have these patients in its trial, and this lead to the ISCHEMIA trial: a government-funded enterprise that was testing two major hypotheses. The first explicit aim of the trial was to randomly assign high-risk patients with large amounts of ischemic myocardium to medical therapy vs. revascularization to finally put to rest the idea that there was benefit to revascularization in any patients with stable coronary disease. If ISCHEMIA didn’t show a benefit of revascularization, the thinking went, there really was no point to ever open arteries, and there seemed to be little point to even doing stress tests.

The other hypothesis being tested was the notion that government funding of comparable effectiveness trials like this that private industry would have no interest in funding would yield clinical benefits to patients and savings to taxpayers. The trial was a miserable failure on both counts, though this would not be apparent if you attended a grand rounds on the topic at your local academic medical center, or read a systemic review from certain corners on the matter.

The ISCHEMIA trial, on the face of it, did not show any benefit when it came to heart attack or mortality in the revascularization arm, leading to the aforementioned widely circulated emails among faculty and grand rounds presentations that “the paradigm of ischemia testing was over”.

But ISCHEMIA has problems galore that should prevent such a conclusion from being drawn. ISCHEMIA can’t really be judged as a good test of high risk ischemia because it didn’t have patients that really were high risk. It turns out that cardiologists have little interest in randomizing high risk patients. We know this because the trial had great difficulty recruiting patients and was hampered by fewer than expected events in the trial. If the trial was working as designed, high risk ischemic patients randomized to medical therapy should have significantly higher event rates than what actually accrued in the trial, and what was expected by trial designers.

Now it’s possible that this reflects the fact that medical therapy has improved significantly, but the tell tale sign here was low recruitment, (trial was reduced from 8000 patients to 5000 patients ) suggesting cardiologists were loathe to randomize actual high risk patients to a conservative strategy (I don’t blame them). Some of this is actually built into the trial, since the exclusion criteria specifically excludes patients with poor heart function (Ejection fraction < 35%) as well as patients with ‘unacceptable’ levels of angina.

Recall that the observational historical data only showed outcome differences between medical therapy and revascularization with total myocardial ischemia >20%. ISCHEMIA’s cut off for inclusion in the trial was > 10% of ischemic myocardium, 35% of enrolled patients had no angina the prior 4 weeks, and only 20% had daily or weekly angina. Of the 5179 patients randomized in ISCHEMIA, only 970 patients had > 15% ischemia reported. So it is a fairly relevant observation that most of the patients in this trial would have been predicted not to have a survival benefit from revascularization. Why would anyone then be particularly surprised that ISCHEMIA wasn’t going to be a home run?

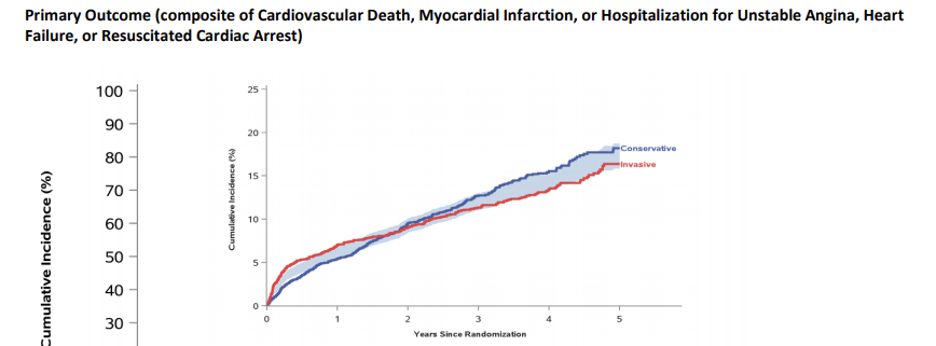

What was a surprise was how the results of ISCHEMIA are impacted by how a heart attack was defined. The following picture plots the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure or resuscitated cardiac arrest vs. time for conservative (medical) therapy, vs. revascularization (invasive) therapy. It is immediately obvious that the revascularization arm is almost immediately associated with more morbid cardiac events reflecting the complications that result from the procedure (periprocedural events). Over time, however, the curves cross, and at the 5 year mark, there are numerically fewer morbid cardiac events in the revascularization arm. The shaded area reflects the 95% confidence interval, and as both curves find themselves in the shaded section, the conclusion as published can only say that there was no significant difference in the primary outcome between the two arms. This is the top-line conclusion many choose to run with and is what leads to excitable presentations about the new paradigm shift that revascularization for stable coronary disease is dead.

But a closer look at what drove the revascularization therapy to be worse initially shows that it was periprocedural heart attacks that drove worse outcomes with revascularization. This is significant because the whole concept of periprocedural heart attacks is shrouded in controversy. Putting a wire in coronary arteries and blowing up balloons to crack coronary plaque results in elevations of cardiac enzymes that are increasingly measured with ever greater sensitivity by blood tests that get better and better at detecting even the tiniest amounts of cardiac damage. It is precisely or this reason Cardiac enzymes are actually not measured routinely in practice after placement of coronary stents because an abnormal result is of little relevance. ISCHEMIA required assessment of these enzymes routinely after procedures and in this particular case, the early cardiac enzyme leak doesn’t translate into an avalanche of worse late come outcomes since there are clearly numerically fewer adverse cardiac events in the invasive arm at 5 year follow up.

What is of relevance to patients and their cardiologists isn’t the periprocedural heart attack the patient is completely unaware of but the spontaneous symptomatic heart attack that occurs well after the procedure. This figure isn’t found in the paper that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It is luckily available in the supplement, and shows that upon excluding the questionably relevant periprocedural heart attack, there is a numerically and statistically significant difference between the two arms that favors the revascularization arm.

Not only are the curves pretty different, but they appear to be separating an ever greater amount over time .

On top of everything, at 5 years, 20% of patients randomized to the conservative strategy do end up getting revascularized, so even if one ignores the spontaneous MI data, it’s more appropriate to say that an initial conservative management strategy is a reasonable approach in this population randomized, rather than “the ischemia paradigm is dead”.

Purists will point out that picking an endpoint like spontaneous MI that wasn’t pre-registered stinks of cherry picking a positive endpoint. We could after all probably find that one of the 12 months of the year revascularization occurred in had a statistically significant difference in outcomes but that would not mean that the ides of March that created fewer events. I would gently push back and suggest that the pre-existing clinical likelihood spontaneous MIs would be different based on revascularization strategy is much different than the likelihood there is something special about the month of March as it relates to revascularization and heart attacks.

That this difference is seen despite the fact that ISCHEMIA ended up with a lower risk population than trialists sought suggests that patient populations that are even higher risk may accrue even greater benefits with an upfront revascularization strategy. So no, the ischemia paradigm is far from dead.

The other particular point raised relates to coronary CTAs (cCTA). These particular tests are the darling of many interested parties that hope to cut into the current giant marketshare of cardiac testing that conventional stress tests enjoy. Just like the COURAGE trial, a test was needed to rule out the super high risk, and in the case of ISCHEMIA, most patients had a coronary CT scan to rule out the presence of really bad disease that wouldn’t allow randomization as well as the occasional false positive stress test. Some have taken the ‘negative’ results of ISCHEMIA to mean that a cCTA is the main test one needs for patients with chest pain. They’d be wrong, of course, because ISCHEMIA as detailed above wasn’t clearly negative. They’d also be wrong because cCTA’s are relatively useless in high risk patients who usually have lots of calcium lining their coronary arteries. Calcium blooms under the gaze of CAT scans, making many scans in the highly calcified indeterminate. The commonly ordered next test for someone with atypical chest pain and an indeterminate cCTA is, of course, a stress test. While cCTAs are excellent tests for the 50 year old with few risk factors and atypical chest pain, they are poor tests for the 65 year old smoker/diabetic with a prior heart attack. It’s also the case that simply defining the anatomy of coronary disease is not that good at making a link to symptoms. There are lots of 50 year olds that walk around with coronary disease that left untouched will die of cancer in their 90s. The vague left arm tingling that prompts the anxious to go to the doctor who yells eureka! upon finding some coronary lesion via a cCTA may not be the happy conclusion the patient needs. Even if a medical therapy route is chosen for treatment, how many trips to the doctor now result because some new symptom may represent progression of disease ?

If I’m the oncall physician who hears that a patient with an 80% coronary stenosis found on CT is having epigastric discomfort, do I see them the next morning or send them to the ER immediately? (This is the argument made for blinding patients and physicians by doing sham intervention trials) Most would choose the latter option, and at some point the artery may very well be stented just to let everyone sleep better. For those who have become CTCA believers as a result of ISCHEMIA, it’s darkly comedic to think that an endeavor that started with a goal of intervening less on stable coronary disease could very well result in the opposite outcome.

The relevant costs to discuss when thinking about why this particular trial is presented the way it is may not be the cost of stress testing annually, but rather the cost of running the ISCHEMIA trial. Reports are that the trial cost $100 million dollars to complete. That is about 100 million reasons to come away with a groundbreaking conclusion after the trial completes. It’s perhaps a bit embarrassing to spend that kind of taxpayer money on a trial that failed to recruit the patients the study was designed at the outset to test, and conclude with a whimper that we still can’t rule out the possibility of benefit of revascularizing patients with high risk stress tests. The clinical cardiologists unburdened by the mandates of statistical purity should take note that even in a population of patients that stress tests were designed to underperform on, there were fewer meaningful heart attacks in those patients with ischemia that underwent an invasive strategy. There are, of course, reasons for this result because patients and their cardiologists were not blinded to having a stent (explained in brief above and a beautiful explainer on blinding and the concepts of faith healing and subtraction anxiety here), but one certainly cannot rule out the possibility of benefit to an invasive strategy.

ISCHEMIA shouldn’t be the last word on the importance of ischemia, regardless of how much the study investigators, and a certain cadre of virtuous academics over-reaching to try to bury stress tests and by extension, revascularization for stable angina, want it to be.

There are smart takes on this topic from academia, but they don’t come from the less-is-more crowd, they come from the subspecialist crowd writing in journals that are read with considerably less frequency than the simple conclusions on ISCHEMIA found in the New England Journal of Medicine (1,2,3,4).

Colleagues, and especially trainees should take the same approach to ‘paradigm shifters’ in medicine that one takes to car salesmen trying to sell you a car based on the the latest advance in seatbelt technology. Run away. Don’t buy what they’re selling. Your patients will thank you.

Anish Koka is a Cardiologist. He is generally allergic to paradigm shifters.

Categories: Uncategorized

It seems that if a stent or other procedure can significantly alleviate symptoms like SOB upon exertion like climbing stairs, patients would view that as a meaningful quality of life benefit even if they are told up front that it probably will not increase their life expectancy. How do most cardiologists view that issue?

Anish

Can you say more of your first image and the observational dataset your reference (>20% at-risk myocardium and death reduction).

Given the era of the study papers (? dates), operative technique, the precision of EF management at the time, and confounding in the analysis, the 20% cut point may be out of date.

What did the Ischemia investigators use as a rationale for patient selection when they opted for 10%. There must be newer data they designed their protocols around to base recruitment on.

Brad

“As such, the discussion that follows will omit any consideration of cost when evaluating the new ‘paradigm shift’ in management of coronary disease that is apparently upon us.”

Really?

“Nonetheless, the over-adoption of some new therapy or technology in American healthcare is supercharged by a third-party payment model that means the eventual self-correction is usually delayed, and the cost of persisting in dead-end pursuits is passed onto future generations of Americans in the form of ever ballooning debt.”