By PHUOC LE, MD and CONNIE CHAN

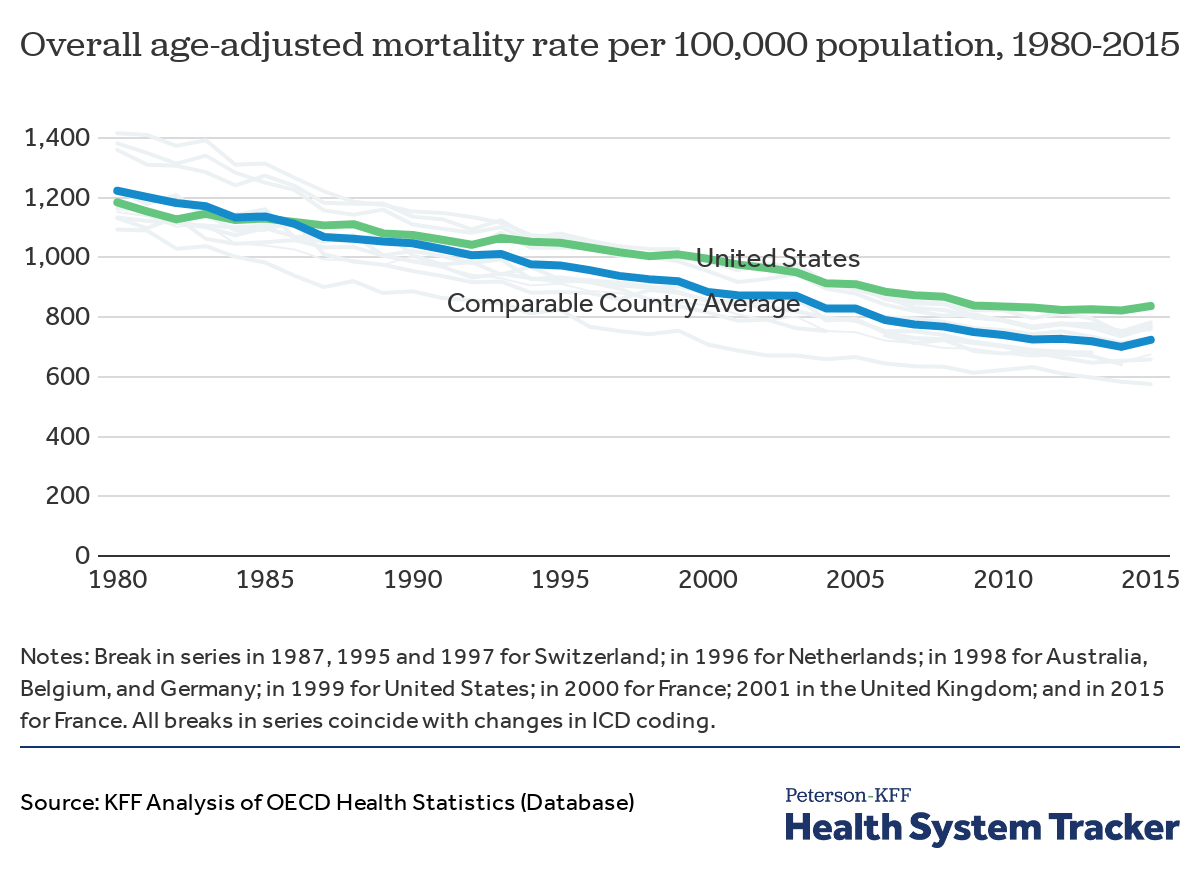

The United States is known for healthcare spending accounting for a large portion of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) without yielding the corresponding health returns. According to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), healthcare spending made up 17.7% ($3.6 trillion) of the GDP in the U.S. in 2018 – yet, poor health outcomes, including overall mortality, remain higher compared to other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. According to The Lancet, enacting a single-payer UHC system would likely result in $450 billion in savings in national healthcare and save more than 68,000 lives.

The expansion of Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) was not the first attempt the United States government made to increase the number of people with health insurance. In 1945, the Truman administration introduced a Universal Health Care (UHC) plan. Many Americans with insurance insecurity, most notably Black Americans and poor white Americans, would benefit from this healthcare plan. During this time, health insurance was only guaranteed for those with certain jobs, many of which Blacks and poor white Americans were unable to secure at the time, which resulted in them having to pay out-of-pocket for any wanted healthcare services. This reality pushed Truman to propose UHC within the United States because it would allow “all people and communities [to] use the promotive, preventative, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need of sufficient quality…, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”

Continue reading…