By KIM BELLARD

We’ve been spending a lot of time these past few years debating healthcare reform. First the Affordable Care Act was debated, passed, implemented, and almost continuously litigated since. Lately the concept of Medicare For All, or variations on it, has been the hot policy debate. Other smaller but still important issues like high prescription drug prices or surprise billing have also received significant attention.

As worthy as these all are, a new study suggests that focusing on them may be missing the point. If we’re not addressing wealth disparities, we’re unlikely to address health disparities.

It has been well documented that there are considerable health disparities in the U.S., attributable to socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, even geography, among other factors. Few would deny that they exist. Many policy experts and politicians seem to believe that if we could simply increase health insurance coverage, we could go a long way to addressing these disparities, since coverage should reduce financial burdens that may be serving as barriers to care that may be contributing to them.

Universal coverage may well be a good goal for many reasons, but we should temper our expectations about what it might achieve in terms of leveling the health playing field.

The new study, by Paola Zaninotto, PhD, et. alia, in The Journals of Gerontology “examined socioeconomic inequalities in disability-free life expectancy.” It compared cohorts from England and the U.S., looking not just at life expectancy but also how healthy those lives were, as measured by presence of disability — the “disability-free” life expectancy. Long study short:

people in the poorest group could expect to live seven to nine fewer years without disability than those in the richest group at the age of 50.

The study looked at men versus women, at different ages, by disability level and wealth status. Most importantly, it compared results for those in England versus the U.S. The authors found that: “we showed that within each country, there was a consistent advantage for people in high socioeconomic groups, particularly for wealth and education, so that they could expect to live a higher number of years without disability.”

Dr. Zaninotto told Yahoo:

We were not surprised. In fact, the reason for looking at wealth and not income is that we know how important a socioeconomic indicator it is. This measure of wealth is based on housing, savings, investments — something that takes a long time to accumulate. It’s a measure of past and present circumstances.

Still, when it came to the similarities between the two countries, Dr. Zaninotto admitted: “It was surprising to find that the inequalities are exactly the same.”

It was surprising because, unlike the U.S., England does have universal coverage. The National Health Service provides access to care to everyone, without financial burdens. There may (or may not) be access issues with the NHS, but they are not, for the most part, financially-driven. And yet the differences of the impact of wealth on health between the two countries are similar.

One could speculate that the wealthy in England are somehow buying their way into better care — perhaps jetting off to Switzerland or even the U.S. — but that is unlikely to account for those seven to nine extra years of disability-free life they are getting.

It’s about the money.

There has been much furor about the obesity crisis in the U.S., with the childhood obesity crisis presenting a ticking time bomb for future health care problems. Same for diabetes. But what we’re not paying enough attention to is that a wealth crisis is looming for younger people as well, which the new findings suggest will result in major health implications.

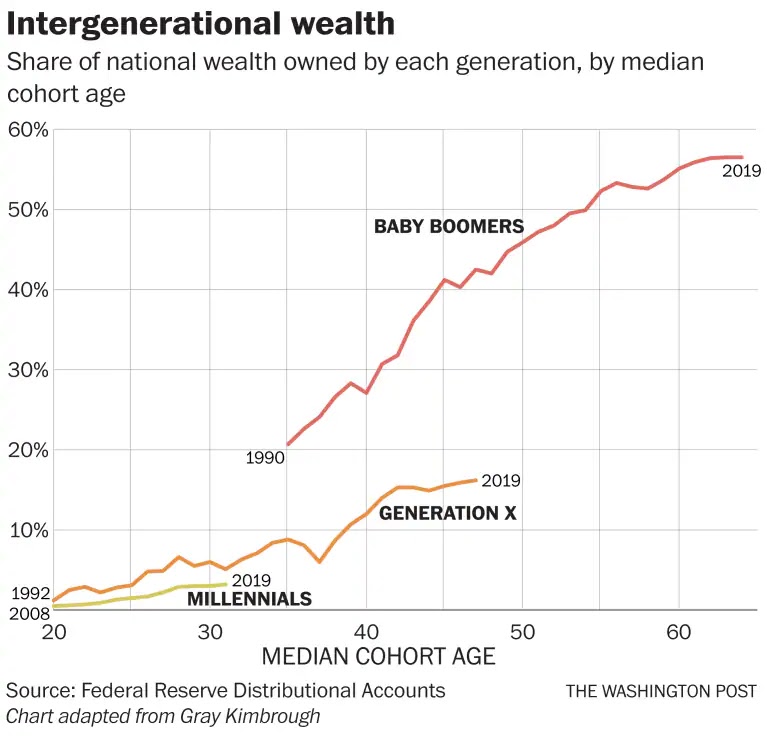

Economist Gary Kimbrough has been studying the upcoming wealth gap, with some alarming results:

Millennials are way poorer than previous generations at their age, burdened by student debt and stagnant wages. Christopher Ingraham, writing in the Washington Post, warns:

It’s a hole they’ll never truly be able to dig out of, given the way that money draws other money to itself via the gravitational pull of compound interest: The less money you start out with, the less you’ll make during the rest of your life.

Some argue that it will all be OK, they’ll eventually inherit significant wealth from their parents –“the Great Wealth Transfer” — but that assumes that those parents won’t end up spending that inheritance on their own health care and other financial needs.

Equally as worrisome, it ignores the adverse health impacts that the reduced wealth is already having on their health. Lack of wealth is not the only hole that you may never be able to dig out of; poor health is at least as hard.

Dr. Zaninotto thinks the results should be a call to action, telling Yahoo:

We really think this inequality should be addressed much earlier in life. When people are older, you can’t give them an education — it really should start much earlier in life. It’s looking at improving opportunities across community and education much earlier and trying to help younger people to buy a house. It seems it is quite important.

The U.S. could, and should, move to universal coverage. It is the right thing to do. We could, and should, find ways to lower costs, both for coverage and for care. It is the right thing to do. But we shouldn’t expect that those actions would level the unequal playing field that wealth creates.

We need to address affordable housing. We need to reduce student debt burdens. We need to ensure people are paid living wages. We need to provide parents with affordable child care options, such as day care, preschool, after-school programs.

Arguably, these are more important than universal coverage, or at least their long-term impacts on health will be greater.

We can’t, and shouldn’t, try to equalize wealth. That’s not what America is about, and not what most Americans want. But there are some aspects of life where wealth should make less of a difference. It shouldn’t dictate opportunity, and, as these findings suggest it does, it shouldn’t determine health.

Kim Bellard is editor of Tincture and thoughtfully challenges the status quo, with a constant focus on what would be best for people’s health.

Categories: Uncategorized

I disagree with “We can’t, and shouldn’t, try to equalize wealth.” Of course, wealth is never totally equal, but in fact wealth in America needs to be majorly more equal than now, with a decent standard of living for everyone (even people who may never be able to take advantage of “opportunity” because of various reasons – I bet most of us have a relative who might work hard but doesn’t have much on the ball).

And yes, wealth equalization, decent housing including a lot of public housing, is at least as important as universal healthcare for health – but that doesn’t make universal healthcare unimportant at all. It just means they are both SUPER-important and we need a candidate who backs radical disruption in both arenas.