BY ANISH KOKA

On March 25th, 1971, the Pakistani army launched Operation Searchlight, a military campaign to brutally suppress a Bengali nationalist movement.

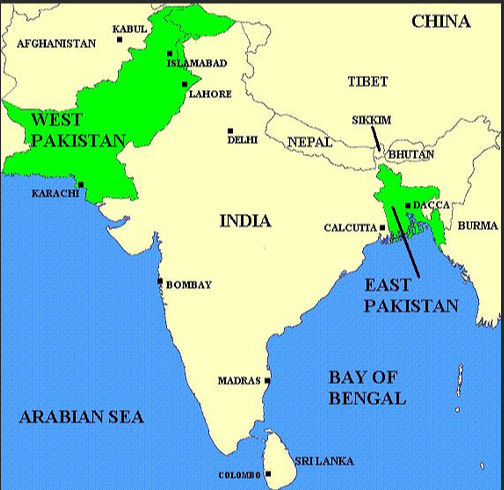

The roots of the genocide lie in the parting gift British rulers gave to the Indian subcontinent at the time of independence in 1947. British controlled India was separated into Hindu majority India and Muslim majority Pakistan. But because there were two dense non-contiguous Muslim majority areas in British controlled India, the muslim majority country of Pakistan was divided into East and West Pakistan.

East and West Pakistan were linked by religion, but little else. East Pakistan was culturally Bengali, and had much more in common with Bengali Hindus than Muslims in West Pakistan. While Bengalis took pride in their culture and language, West Pakistani’s looked down on the Bengali’s because it was deemed to be too influenced by Hindu culture. While Bengali muslims may have identified themselves with Pakistan’s islamic project, by the 1970s many in East Pakistan had given priority to their Bengali ethnicity over their religious identity, desiring a society more in accordance with Western principles of secularism and democracy. A growing opposition in East Pakistan strongly objected to the Islamist paradigm being imposed the West Pakistani state.

But West Pakistan controlled the military, and formed much of the ruling elite after the partition in 1947. In a move designed to send a message to Bengali speaking East Pakistani’s , the founding father of Pakistan, Muhammad Jinna even made Urdu the national language of all of Pakistan, and branded those opposed as enemies of the State.

Continue reading…