It’s one of those calls you never want to get as an electrophysiologist:

It’s one of those calls you never want to get as an electrophysiologist:

“Doc, I got four shocks from my device yesterday.”

“What were you doing at the time?”

“Working outside.”

“Wasn’t it about a 100 degrees and humid then?”

“Yes.”

“Were you lightheaded before the event?”

“Not too bad… I stopped what I was doing and got better. Should I come in to the ER?”

“This happened yesterday?”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you come in then?”

“Well I started to feel better…”

“Do you know how to upload the information from your device at home?”

“You mean using that thing next to my bed?”

“Yes.”

“I think so.”

“Okay, why don’t you go do this and we’ll call you right back after we have a chance to view the information you send us.”

“Okay. Thanks, doctor.”

So I waited about 15-20 minutes, then checked the Medtronic Carelink app on my iPhone.

This application lets doctors and device management personnel view all of the information uploaded from pacemakers and defibrillators that we normally review in our device clinics on our iPhones instead. I hadn’t had much need for this, or so I thought, until now. I thought it would be cool for patients to see what their authorized doctors can view on their iPhones when things like this occur, so I took some screenshots.

Booting the app:

Click on any image to enlarge

The login screen:

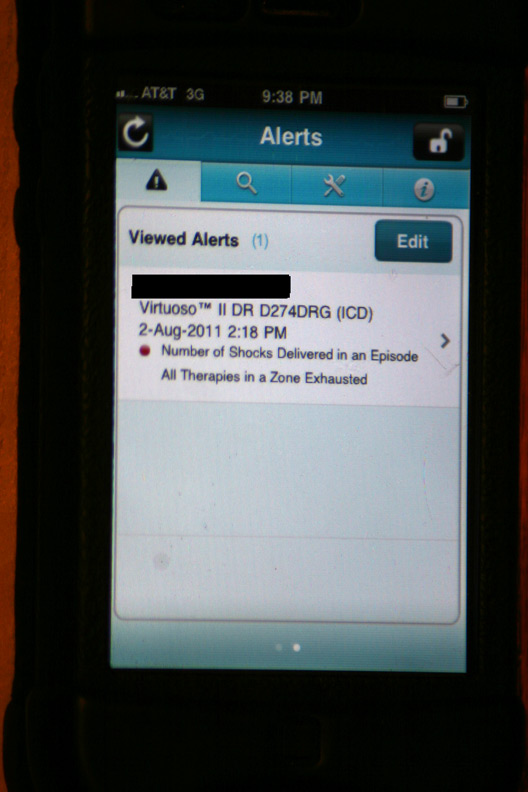

The initial alert that appeared after logging in:

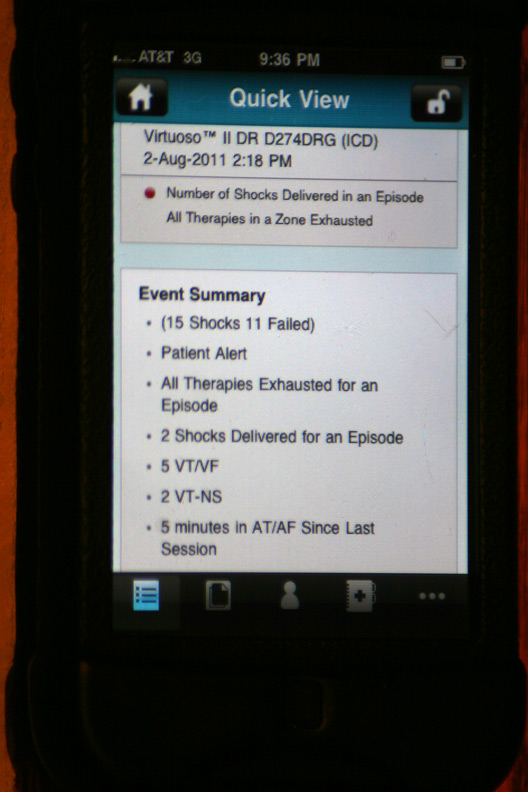

The gory details of that event displayed after touching the above alert (Holy cow! He had a lot more than four shocks!):

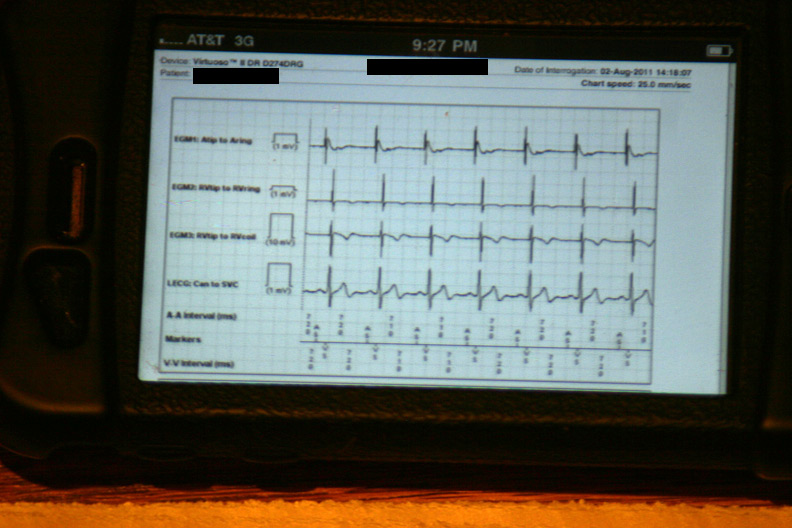

The data were then loaded from the event in a 42-page unprintable pdf file (HIPAA prevents printing, I guess). Page one contained the various atrial and ventricular electrograms (signals from the wires in his heart) at the time the data were transmitted:

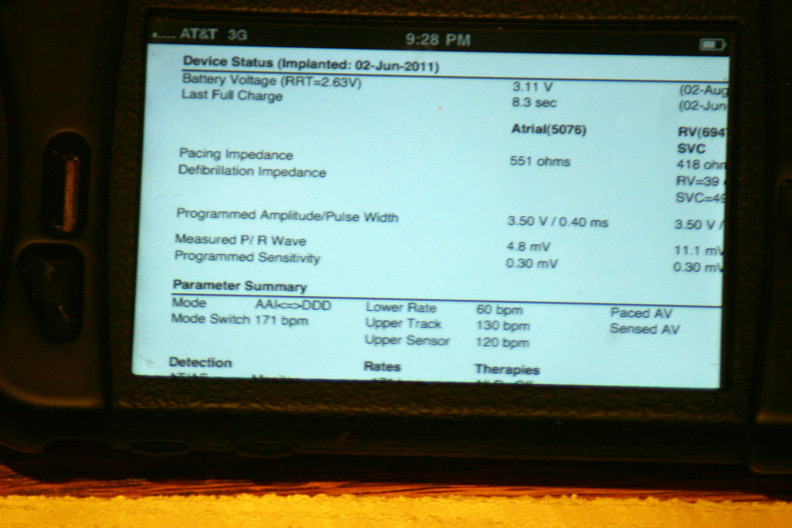

A few of the basic programmed parameters and remaining battery life (Whew, plenty left!):

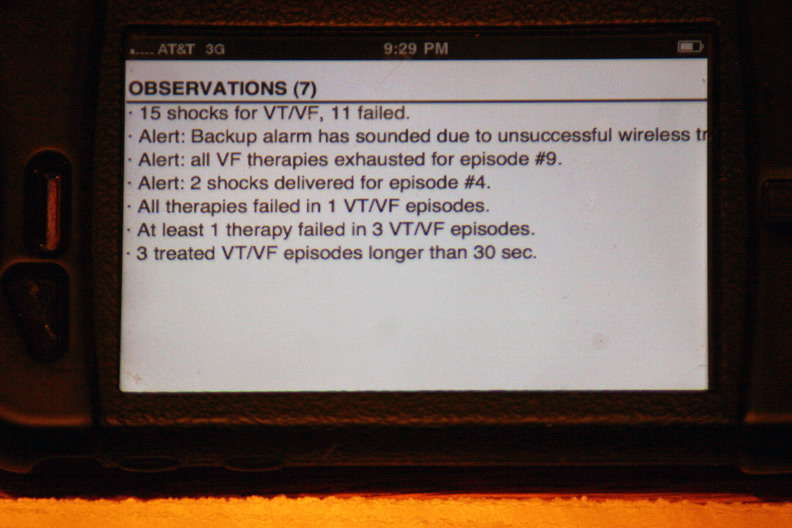

The device’s seven “observations” classifying the types and numbers of therapies:

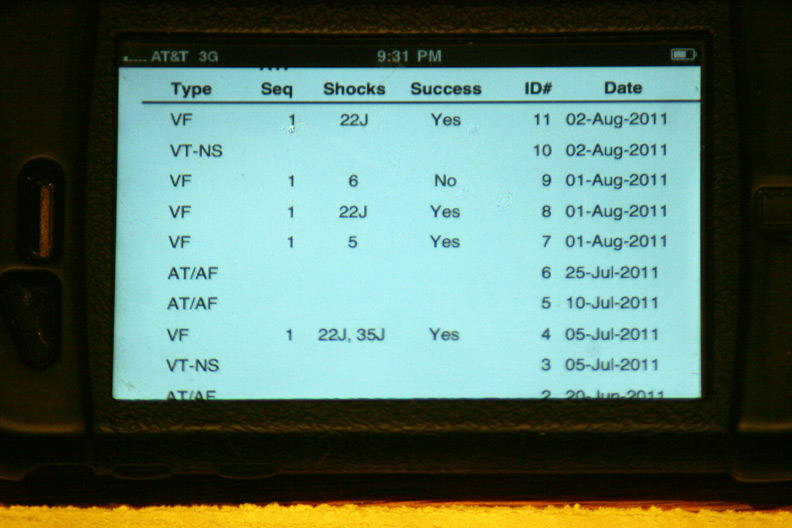

More specifics regarding the time and number of shocks at each event:

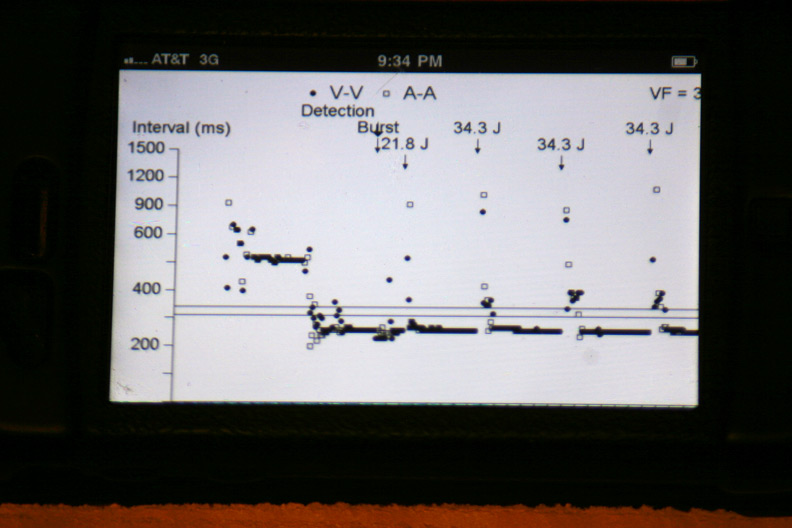

The atrial and ventricular inter-electrogram interval plot for the most recent event with repetitive shocking:

Zooming in on the plot of atrial (squares) and ventricular (circles) intervals at the intitiation of the event (Who started things?):

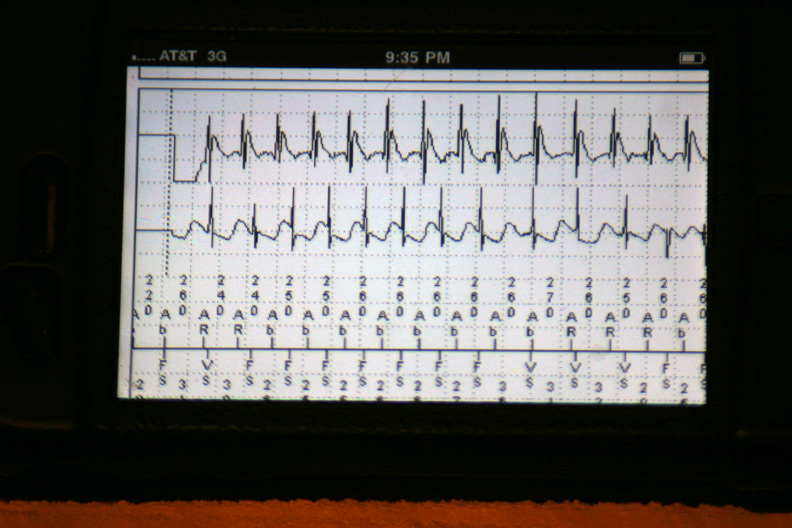

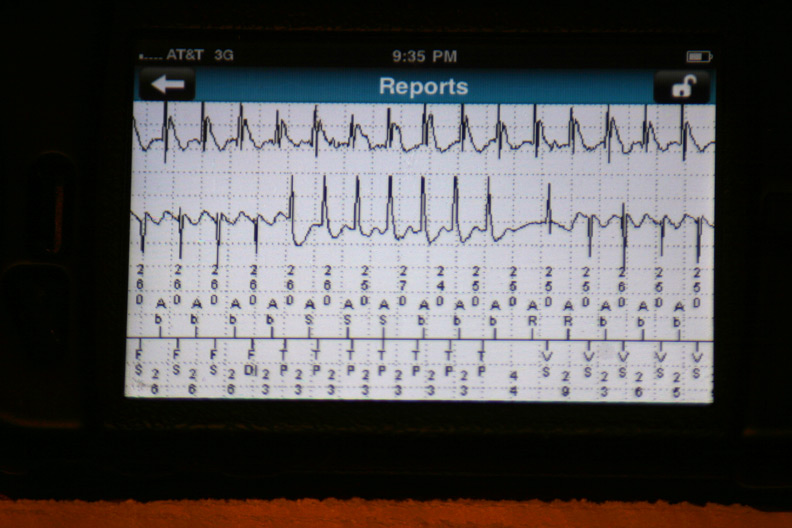

The atrial and ventricular electrograms obtained during one of the events (Is that Wenckebach block?):

The effect of antitachycardia pacing during the event: the ventricle is paced but had no effect on the atrium driving the ongoing event:

The other events disclosed similar findings. It appeared each of these shock therapies were delivered as a result of a very fast atrial tachycardia that was able to conduct to the ventricle, rather than a ventricular rhythm problem.

Of course, there is a slight problem that presents itself to doctors and their business administrators when we use this very cool technology: it’s all done for free. Still, the ability to review this important clinical information untied to a hard-wired computer terminal offers important advantages to our increasingly mobile physician workforce and, in this case, prevented an unnecessary emergency room visit.

-Wes

Epilogue: The patient was contacted by phone after reviewing this information. He as told he did not have to go to the Emergency Room. Instead, significant adjustments were made to his medication regimen over the phone. He was seen the next morning in our device clinic to reset the alarm that was triggered when his device exhausted all its therapies in one event. No further arrhythmias had transpired and discussions regarding alternate medical or ablative therapies are pending.

P.S.: Sorry patients, the while the app can be downloaded from the Apple iTunes App store for free, its use is restricted to authorized care providers only. Maybe when implantable devices carry memory bins for uploaded digital music…

Westby G. Fisher, MD, (aka Dr. Wes) is a board certified internist, cardiologist and cardiac electrophysiologist practicing at NorthShore University HealthSystem in Evanston, IL. He is also a Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine. He blogs at Dr.Wes, where this post originally appeared.

Categories: Uncategorized